From Sequential Bottlenecks to Concurrent Performance: Optimizing Log Processing at Scale

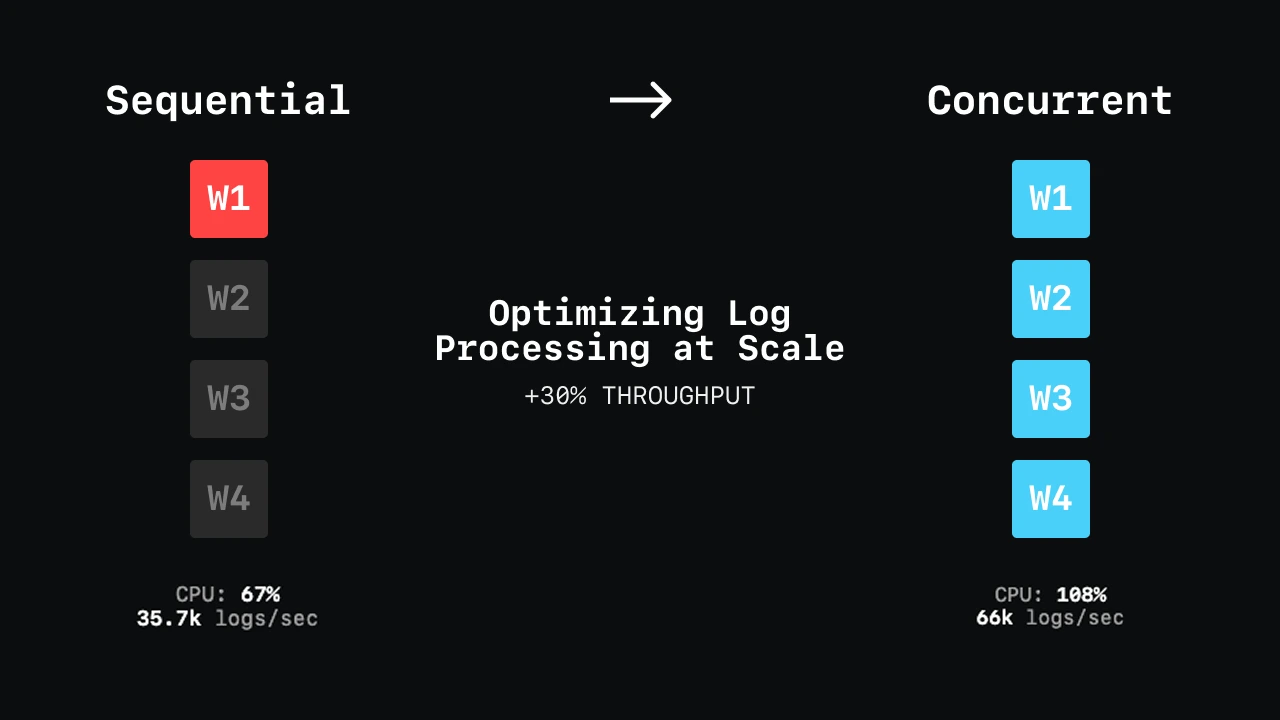

We optimized log processing pipeline by moving from sequential to concurrent processing at the entry level, achieving 30% higher throughput and better resource utilization without increasing infrastructure costs.

When customers start sending millions of logs per minute, you need both horizontal and vertical scaling capabilities. While we can horizontally scale collectors across distributed systems to handle millions of logs, we discovered that our individual collectors weren't effectively utilizing vertical scaling when we added more CPU or memory. The performance didn't improve proportionally.

This is the technical story of how we diagnosed a fundamental sequential processing bottleneck and moved to concurrent processing at the entry level.

The Problem: Vertical Scaling Wasn't Working

The Scaling Challenge

Our collector was not working better when we were vertically scaling. Any piece of software, if you give it more memory or more CPU, it should start utilizing that. But our collector was not doing that.

Resource utilization challenges became noticeable at 1 million logs per minute. At this threshold, we would see significant lag that could persist for hours, making logs unqueryable during critical periods.

Resource Utilization Analysis

Despite allocating substantial resources, we observed concerning utilization patterns:

Sequential Processing Performance:

- CPU Usage: 2,694m out of 4,000m allocated (67% utilization)

- Memory Usage: 6.83GiB out of 12GiB allocated (57% utilization)

- Processing Rate: 35.7k logs/second

- Consumer Lag: 2,650 messages

This represented a significant optimization opportunity: the allocated resources had much more potential that wasn't being fully realized.

Root Cause: Sequential Processing Architecture

The Sequential Bottleneck

The core issue was architectural. Being OpenTelemetry-native, we followed the standard sequential processing approach from the OTel collector. However, this creates a processing tunnel where logs are handled one by one.

The processing worked like this:

// Simplified representation of the sequential processing

func processLogs(entries []LogEntry) {

for _, entry := range entries {

// Process each entry one by one - basic for loop

processedEntry := transformEntry(entry)

// Send to next stage

}

}

This created a "tunnel" effect where despite having multiple CPU cores available, only one core was actively processing logs while others remained largely idle.

The situation was like having a barrage (like an ocean) and you're trying to fit it into a tunnel. There is a huge barrage of volume, and we are processing it via a very small pipe.

Scaling Challenges During Peak Load

During extreme load conditions (consumer lag reaching 10,000+ messages per second), we needed to make operational adjustments to maintain system stability. Our approach involved temporarily scaling back processing to allow the system to recover, then gradually resuming normal operations.

During these scaling adjustments, if customers were ingesting 6 million logs per minute, a significant volume of logs would be stored but remain unqueryable until normal processing resumed.

The Solution: Concurrent Processing at Entry Level

Moving to Concurrent Processing

The solution was to process entries concurrently rather than sequentially. Instead of processing logs one by one (first, then second, then third, then fourth), we changed it so that one, two, three, and four would be done simultaneously.

Implementation Approach

// Concurrent processing at entry level

func processLogsConcurrently(entries []LogEntry, workerCount int) {

entryChan := make(chan LogEntry, len(entries))

resultChan := make(chan ProcessedEntry, len(entries))

// Start workers equal to CPU count

for i := 0; i < workerCount; i++ {

go func() {

for entry := range entryChan {

processed := transformEntry(entry)

resultChan <- processed

}

}()

}

// Distribute work

for _, entry := range entries {

entryChan <- entry

}

close(entryChan)

// Collect results

for i := 0; i < len(entries); i++ {

<-resultChan

}

}

Worker Pool Sizing

The number of workers equals the number of CPUs we provide to our collector. In our staging cluster, it's 4 CPUs, but for customers, we tend to give 8 CPUs, 16 CPUs - based on their needs.

No Ordering Guarantees

A key design decision was removing ordering requirements. We don't control after which worker we schedule the next task. We can schedule it after any one, whichever finishes the job first.

This trade-off was acceptable since log storage systems typically don't require strict ordering, and it significantly improved throughput.

Performance Results

Dramatic Improvement

After implementing concurrent processing:

- CPU Usage: 4,352m out of 4,000m allocated (108% utilization)

- Memory Usage: 12.16GiB peak, 6.76GiB average

- Processing Rate: 66k logs/second peak, 47k logs/second average

- Consumer Lag: 2,650 messages (reduced)

30% Performance Gain

The processing rate increased from 35.7k to 46k logs/second (with peaks up to 66k), representing a 30% improvement in throughput with the same infrastructure.

Better Resource Utilization

Most importantly, we achieved full utilization of allocated resources. The CPU usage reaching 108% indicates efficient utilization with burst capacity, while memory usage showed we could handle peak loads effectively.

Instance-Level Optimization

The testing was conducted on a 4-core machine. While the per-instance infrastructure remained unchanged, we achieved significantly higher throughput. This means fewer instances are needed for the same workload, reducing overall infrastructure cost while increasing performance. The optimization unlocks more value from each machine, improving scalability and operational efficiency.

Testing at Scale

High-Volume Testing

We tested the solution under extreme conditions, generating 6 million logs per minute to validate the concurrent processing approach.

Eliminating Operational Adjustments

The concurrent processing eliminated the need for manual scaling adjustments during traffic spikes. Previously, during high load, we would temporarily scale back processing and wait for 10 to 20 to 30 minutes for the system to stabilize. This meant that during peak periods, significant log volumes would experience delayed pipeline processing.

Implementation Details

Technical Implementation and Impact

- The implementation uses a worker pool pattern where worker count equals CPU cores allocated. Each worker processes entries independently, and results are collected without order guarantees. This approach allows all CPU cores to actively process logs simultaneously, eliminating the tunnel effect where workers would block waiting for others to complete.

- Moving from sequential to concurrent processing provides natural scalability with CPU allocation. More cores mean more concurrent workers, and the approach scales linearly with available resources.

- Memory usage patterns showed peak usage during bursts (12.16GiB) with stable average usage (6.76GiB), demonstrating efficient resource utilization without memory leaks during sustained load. Error handling is isolated per worker, so individual entry failures don't stop other workers, providing graceful degradation under load.

- The most significant operational improvement was eliminating the need for manual scaling adjustments during traffic spikes. The system now maintains consistent performance under varying load conditions, providing better resource return on investment and predictable performance characteristics.

Key Engineering Insights

Simply adding more CPU or memory won't help if the software architecture doesn't support concurrent processing. Having resources allocated doesn't mean they're being utilized effectively. Many systems inherit sequential processing models that don't scale with modern multi-core architectures, making concurrent processing essential for performance.

Relaxing ordering requirements can provide significant performance benefits in distributed systems where strict ordering isn't necessary. This architectural trade-off was key to achieving the 30% throughput improvement.

Conclusion

By moving from sequential to concurrent processing at the entry level, we achieved:

- 30% sustained throughput improvement (35.7k to ~46k average, with 66k peaks)

- Better resource utilization (67% to 108% CPU usage)

- Eliminated operational adjustments during traffic spikes

- Cost efficiency: same infrastructure, better performance

The key insight was recognizing that vertical scaling requires concurrent processing architecture. Sequential processing creates bottlenecks that can't be solved by adding more resources.

This optimization demonstrates the importance of understanding your system's architectural constraints and making design changes that align with modern multi-core computing capabilities.

Try these optimizations in your own environment and join our community to discuss performance engineering challenges.