I built an MCP Server for Observability. This is my Unhyped Take

Recently, I read a blog titled “It’s The End Of Observability As We Know It (And I Feel Fine)”, which discussed MCP servers in observability and how these systems would potentially be the “end of observability”.

As someone who has spun up an MCP server for an observability backend [SigNoz] and as someone who has been in the space for a while, I certainly do not think so. This is my honest, raw take on why MCP servers for observability may not be worth the hype, if it’s hyped at all, subject to moot, of course.

This is not a rebuttal, but a healthy debate which is vital to the sustenance of intelligence on Earth and critical to evaluating engineering paradigms.

Now, what is this MCP thing?

Enter Model Context Protocol, commonly referred to as MCP.

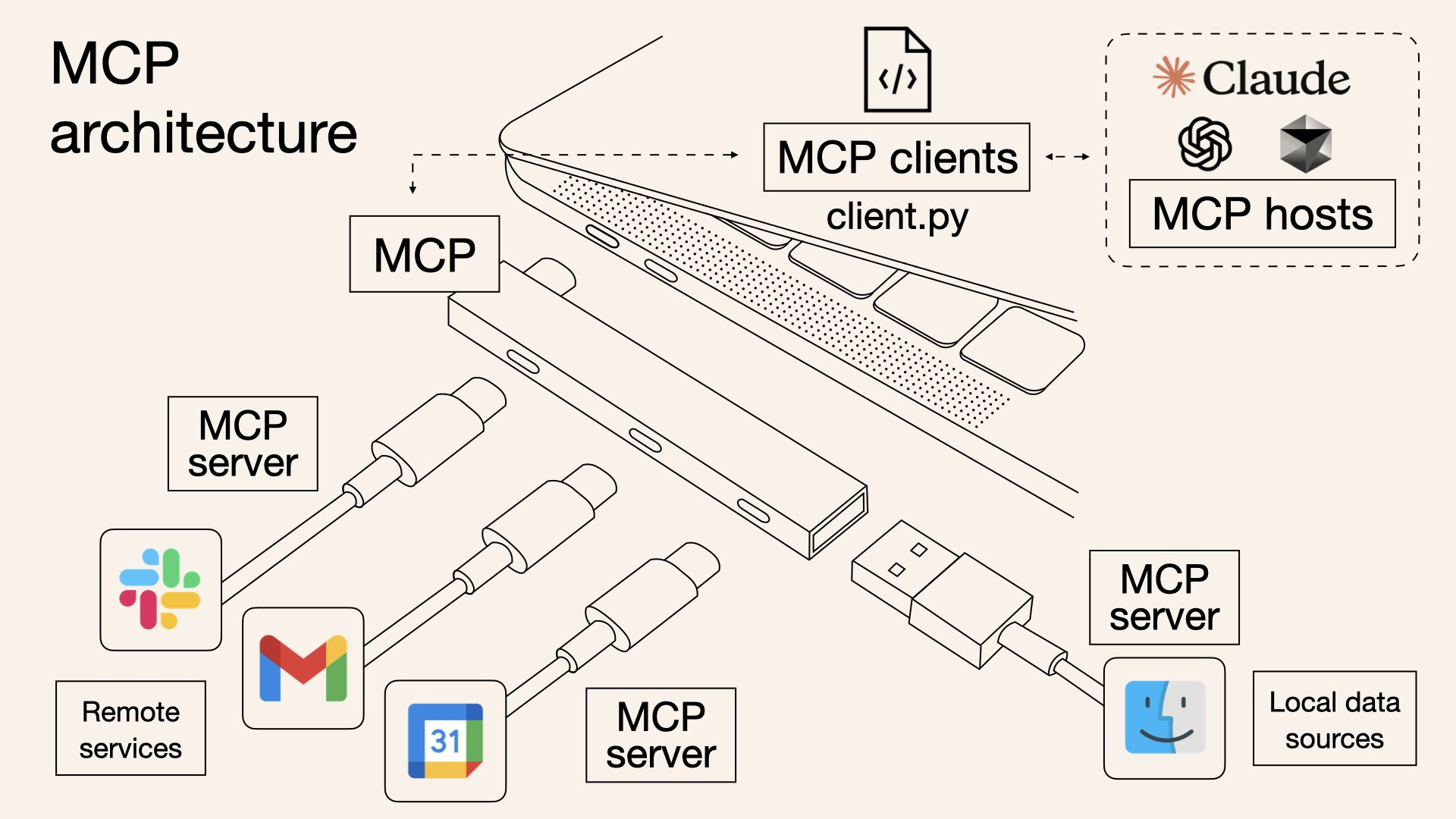

For those who are not familiar, MCP, originally developed by Anthropic, is an open standard that defines how AI agents or LLMs [think Claude etc] can connect to external tools and data sources in a uniform way.

One of the most powerful aspects of MCP is that you can create an MCP server once and use it with any compatible agent of your choice. It decouples the server [which exposes the tools] from the AI model itself. This makes MCP analogous to USB-C; you build a standard port once, and any device [agent] that supports it can plug in and start using it.

At its core, I think MCP is not revolutionary in itself but rather evolutionary. It’s a universal standard, and it makes things easier and keeps the engines running forward.

What does it mean to have an MCP server for your observability backend?

Suppose, You see a spike in memory usage in your cart_service dashboard. Some of your next steps would be to look around for a memory leak in logs or traces and reach a possible conclusion. With MCP in the frame, you can ask your AI agent why the spike occurred, and then it uses the MCP tools to make API calls and reach a couple of hypotheses.

This is the simplest way I can put across the “role” an MCP server plays in an observability stack.

Here’s a quick demo of a very basic MCP server I spun up for SigNoz with Cursor as my AI agent.

MCP servers for observability may not be the holy grail it is hyped to be

Let me get to the crux of this blog. I would like to draw an analogy (or parallelism?) between P vs NP problems from my automata theory lectures and the role of MCP servers in the observability space. Here’s my two cents,

- (P) refers to problems that can be solved quickly by a computer.

- (NP) refers to problems where, if you are given a potential solution, you can verify it quickly.

Root Cause Analysis comes under a set of problems that are not easy to solve (not P) but once a solution, or say a hypothesis, is generated, it becomes easier to verify it [although there are exceptions]. That is, they can be labelled as an (NP) problem. MCP servers, in my opinion, do a decent job of identifying plausible hypotheses for RCA in most cases, with room for exceptions.

But sometimes, the process of manually verifying the generated hypotheses is as cumbersome as finding the solution yourself in the first place. Let’s examine this in greater detail.

When does the LLM get it wrong?

Usually, if the issue is familiar to the LLM, if it knows of it and there is sufficient context for it in the LLM’s training data, it’s insanely good at reaching the correct hypotheses quickly. That is, when the problem space overlaps with the LLM’s knowledge base. For example, a pod CrashLoopBackOff due to the wrong image pull or memory limit can be easily spotted by an LLM. However, when the issue is novel, the chances of an LLM getting RCA right today are close to zero. Let me back up my argument with facts. Here’s the citation from a conference paper, “AIOps for Reliability: Evaluating Large Language Models for Automated Root Cause Analysis in Chaos Engineering”,

We simulate eight real-world failure scenarios in a controlled e-commerce environment and assess LLMs’ performance in zero-shot and few-shot settings compared with Site Reliability Engineers. While LLMs can identify common failure patterns, their accuracy is highly dependent on prompt engineering. In zero-shot settings, models achieve moderate accuracy (44–58%), often misattributing harmless load spikes as security threats. However, few-shot prompting improves performance (60–74% accuracy), suggesting that LLMs require structured guidance for reliable RCA.

Despite their potential, LLMs are not yet ready to replace human SREs, who achieved over 80% accuracy due to hallucinations, misclassification biases, and lack of explainability. The findings highlight that LLMs can be co-pilots in incident response, but human oversight remains essential.

Zero-shot prompting refers to the method of asking an LLM to perform a task without providing any prior examples on how to do it. On the other hand, few-shot prompting is the technique of providing 2-3 examples of performing a task; in-context learning.

So, let me paint a picture: in that intense moment of an escalation, you're working on prompts to make your LLM coupled with MCP to brainstorm hypotheses for you, and then verifying those hypotheses manually.

Tsk tsk. Sounds like a bad idea.

This leads me to my next point, which is also a well-established fact.

Hallucinations

LLMs hallucinate. A lot. Maybe it’s slightly schizophrenic?

A condition that I never thought would ever be associated with a machine, but it seems like LLMs themselves have quite a few mental health issues to cater to.

When an LLM comes up with the wrong reasoning, it does so with a sense of confidence and conviction that becomes difficult to take note of unless you are a veteran in what you do. Or you are good at catching lies. It is a dangerous property in a high-stakes context like incident management or RCA. An LLM-based RCA might calmly assert a root cause that sounds convincing [“A cache miss storm likely causes the outage due to XYZ”], leading the team to pursue that line of inquiry and potentially ignore the real issue until much later.

Of course, we’ve progressed to a point where the amount of hallucination is less and precision is more, but ✨ trust issues ✨ exist.

Let me also point out to you how these hallucinations could aggravate in a tool-chaining system like an MCP system or an agentic model.

Deviations and Alignments

If an AI agent suggests Service X is likely the culprit due to a spike in latency, an engineer must dig into dashboards, logs, or traces to confirm that.

If the suggestion is wrong [or one of many], you’ve spent precious time on a false lead. In worst cases, verifying multiple AI-proposed hypotheses in sequence can feel like exploring an exponentially growing search tree of possibilities, much like brute-forcing an NP problem.

Consider a scenario where an LLM-based agent makes 8 MCP tool calls in a troubleshooting session, and at each step, there are ~3 plausible interpretations of the data [only one of which is correct]. The space of possible reasoning paths through those steps is on the order of 3^7 [over 2,000 paths], and any deviation at one step leads the AI down a wrong branch.

And we are being generous.

In theory, the agent should pick the correct path, but in practice, each step carries a risk of error. This combinatorial explosion of possibilities means the agent could easily go astray unless it stays perfectly aligned with the ground truth at every step, a very challenging and quite impossible requirement. Without careful constraints or a human-in-the-loop to course-correct, the AI might output a confident analysis that is subtly off-track, leaving you to double-check each detail.

No Real World Model

Let’s look at this recent study from MIT. An LLM was trained with text on the NYC city map.

The model was perfectly capable of providing near-perfect driving directions in New York City, yet it hadn’t learned a correct map of NYC. When the researchers introduced a slight change [closing some roads for a hypothetical detour], the model’s navigation performance plummeted because its hidden “mental map” was full of errors.

In other words, the model appeared to know the city when everything was normal, but that was an illusion. It had no coherent internal model of the street grid. This analogy can be easily extended to observability systems where an LLM might seem to know your system’s behaviour under normal conditions [e.g. it can predict that high CPU on Service Y often coincides with a cache miss in Service Z, because it’s seen that pattern]. But if something changes, say a new deployment alters dependencies, or an outage causes a novel cascade the LLM can fail in unpredictable ways.

Do we have a conclusion?

We are living in the AI era, and MCP servers play a significant role in providing an additional interface between us and observability platforms. For tasks like converting natural language queries to PromQL or LogQL, an MCP-powered LLM can perform exceptionally well, as the task has tight semantics and predictable output format along with ample training data to provide it context.

We might witness a future[or present?], where we spend less time building and staring at graphs and more time prompting LLMs to brainstorm viable hypotheses. We will see the evolution of an agentic layer emerge and become increasingly capable in various aspects of observability, but still requiring a good amount of manual intervention and verification.

Ultimately, MCP-powered agents are not bringing us closer to automated problem-solving. They are giving us sophisticated hypothesis generators. They excel at exploring the known, but the unknown remains the domain of the human engineer. We're not building an automated SRE; we're building a co-pilot that can brainstorm, but can't yet reason. And recognising that distinction is the key to using these tools effectively without falling for the hype.

And with this, I rest my case.