Container Observability - Metrics, Logs, and Traces with OpenTelemetry

Container Observability is the practice of collecting and correlating metrics, logs, and traces from containerized applications to understand their internal state. Containers are ephemeral. They spin up, serve traffic, and get terminated, often within seconds. Traditional monitoring tools that rely on static host-based agents do not work well in this environment because the containers can disappear before an alert even fires.

This guide covers what container observability is, how it differs from container monitoring, the key signals you need to collect, the challenges specific to containerized environments, and how to set it up using an open-source framework like OpenTelemetry.

What is Container Observability?

Container observability is the ability to understand what is happening inside your containers and why. It relies on three types of telemetry data:

- Metrics - time-series measurements that reveal trends and saturation (CPU, memory working set, request rate, latency percentiles, error rate).

- Logs - timestamped events that provide context and details (application output, exceptions, stack traces, container stdout/stderr).

- Traces - request-level timelines that show how a single request moves through multiple services, including hop-by-hop latency, dependencies, and where time is spent.

These three signals are often called the three pillars of observability. Individually, each signal tells you something. Correlated together, they let you answer questions like: "The p99 latency for the checkout service spiked at 14:32, which downstream container was slow, what error did it log, and which specific request was affected?"

Container Observability vs Container Monitoring

Monitoring and observability provide different types of visibility into container platforms. Monitoring tracks predefined health signals, while observability uses telemetry data and correlate them to reason about system behaviour.

| Aspect | Container monitoring | Container observability |

|---|---|---|

| Core goal | Detect and alert on known conditions using collected telemetry (dashboards/alerts over quantitative signals). | Enable deeper understanding of system behaviour by using multiple telemetry signals that can be correlated. |

| Primary question | “Is it healthy / within expected bounds?" (monitoring is centered on collecting/aggregating/displaying real-time quantitative data). | “Why is it happening / what’s the causal path?" (correlation across traces/metrics/logs enables causal and cross-service reasoning). |

| Typical signals emphasized | Often metrics-first for infra and platform components. | Commonly framed around logs, metrics, traces as core signal types for observability. |

| Correlation capability | Correlation may exist depending on tooling, but monitoring as defined does not require cross-signal correlation, it focuses on collecting/processing/aggregating/displaying data. | Explicitly supports correlating traces, metrics, and logs via context propagation (trace/span IDs etc.). |

| Scope (what it typically focuses on) | Commonly focuses on platform/service health indicators suitable for alerting and dashboards (SRE monitoring definition + dashboards/alerts). | Extends naturally to distributed request flows where tracing builds causal info across services and boundaries. |

| Troubleshooting workflow (typical) | Often starts from an alert/dashboards (monitoring → alert → investigate). | Often starts from a symptom then uses correlated telemetry to follow causality across services. |

Key Metrics to Track in Containerized Environments

Container platforms emit a large number of metrics, but only a subset is consistently useful in production. The metrics below focus on signals that directly reflect resource pressure, stability, and request behaviour.

Resource Metrics

Resource metrics come from the container runtime (containerd, Docker) or the orchestrator (Kubernetes). They tell you how much CPU, memory, network, and disk the container is consuming.

Key metrics to track:

| Metric | What it measures |

|---|---|

container_cpu_usage_seconds_total | Total CPU time consumed by the container (seconds). |

container_memory_working_set_bytes | The container’s working set memory (memory considered not easily reclaimable). |

container_network_receive_bytes_total / container_network_transmit_bytes_total | Cumulative network bytes received/transmitted per container. |

container_fs_writes_bytes_total | Cumulative bytes written to filesystem by the container. |

Application-Level Metrics (RED Metrics)

For each service running inside your containers, track the RED (Rate, Errors, and Duration) metrics. These are the metrics your SLOs should be built on. A container might have healthy resource usage but still serve errors or respond slowly due to downstream dependencies.

The actual metric names depend on your instrumentation. Here are the specific metrics for OpenTelemetry (OTel semantic conventions) setups:

| RED Signal | OpenTelemetry Metric | What It Tells You |

|---|---|---|

| Rate | http.server.request.duration | Requests per second. |

| Rate | http.server.active_requests | Number of active requests at any moment. Useful for detecting concurrency saturation. |

| Errors | http.server.request.duration filtered by error.type attribute or http.response.status_code >= 500 | Failed requests. Filter by status code or error.type (e.g., timeout, java.net.UnknownHostException). |

| Duration | http.server.request.duration | Latency distribution. Compute percentiles using your backend's quantile functions (e.g., histogram_quantile() in PromQL, or equivalent functions in your observability platform's query language). |

| Request Size | http.server.request.body.size | Size of incoming request payloads in bytes. Useful for detecting abnormally large requests. |

| Response Size | http.server.response.body.size | Size of response payloads. Helps identify endpoints returning excessive data. |

Kubernetes-Specific Metrics

In Kubernetes, many production issues surface as state and lifecycle problems rather than simple resource exhaustion. The following metrics track restarts, termination reasons, pod phase, and replica availability to expose those conditions.

| Metric | What it tells you |

|---|---|

kube_pod_container_status_restarts_total | Cumulative restart count of a container. |

kube_pod_container_status_last_terminated_reason | The reason the container last terminated (e.g., OOMKilled, Error, Completed). |

kube_pod_status_phase | Current lifecycle phase of the pod (Pending, Running, Succeeded, Failed, Unknown). |

kube_deployment_status_replicas_available | Number of available replicas in a Deployment (ready and serving). |

Container Observability with OpenTelemetry

OpenTelemetry (OTel) is an open-source observability framework under the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) that provides a vendor-agnostic standard for generating, collecting, and exporting telemetry data. It emerged from the merger of OpenCensus and OpenTracing with a singular goal: to unify how applications are instrumented across languages, frameworks, and environments.

Containers are ephemeral and constantly changing, so traditional, host-based monitoring breaks down quickly. OpenTelemetry addresses this by providing standardized semantic conventions for container and Kubernetes metadata (such as container.id, k8s.pod.name, and k8s.namespace.name), ensuring consistent telemetry collection across your containerized infrastructure at any scale.

Instrumenting Container Environments with OpenTelemetry

You can instrument your container environments with OpenTelemetry by deploying the OpenTelemetry Collector, a vendor-agnostic agent that receives, processes, and exports telemetry data. The setup varies depending on your environment.

For Docker, you configure receivers like docker_stats to collect container metrics (CPU, memory, network I/O) and the filelog receiver to capture container logs from /var/lib/docker/containers. For a complete walkthrough, follow our tutorial on Monitoring Docker containers with OpenTelemetry.

For Kubernetes, the approach involves deploying collectors as DaemonSets for node-level metrics and logs, and as Deployments for cluster-level metrics and events. These collectors use receivers like kubeletstats, k8scluster, and k8sevents to gather telemetry from across your cluster. For step-by-step implementation, refer to our Kubernetes Observability with OpenTelemetry Guide.

Collecting Logs from Containers

Container logs work differently from traditional application logs. Containers write to stdout and stderr, and the container runtime (containerd or Docker) captures these streams and writes them to log files on the host node, typically at /var/log/containers/ in Kubernetes.

There are two main approaches to collecting these logs:

Node-level log collection (DaemonSet pattern) : A log collector agent runs as a DaemonSet on each node, tailing log files from

/var/log/containers/and forwarding them to an observability backend like SigNoz. This is the most common approach because it requires no changes to your application containers.Sidecar pattern : A log collector container runs alongside your application container in the same pod. This approach is useful when your application writes logs to files inside the container rather than to stdout, the sidecar reads these files and forwards them to your backend.

Using SigNoz for Container Observability

Once your telemetry data is flowing through the OpenTelemetry Collector, you need a backend to store, query, and visualize it. SigNoz is an all-in-one observability platform built natively on OpenTelemetry that stores metrics, logs, and traces in a single backend (ClickHouse) and provides a unified UI to query all three signals.

To send data from the OpenTelemetry Collector to SigNoz Cloud, update the exporter configuration:

exporters:

otlp:

endpoint: "ingest.<region>.signoz.cloud:443"

tls:

insecure: false

headers:

"signoz-ingestion-key": "<your-ingestion-key>"

With data flowing into SigNoz, you get:

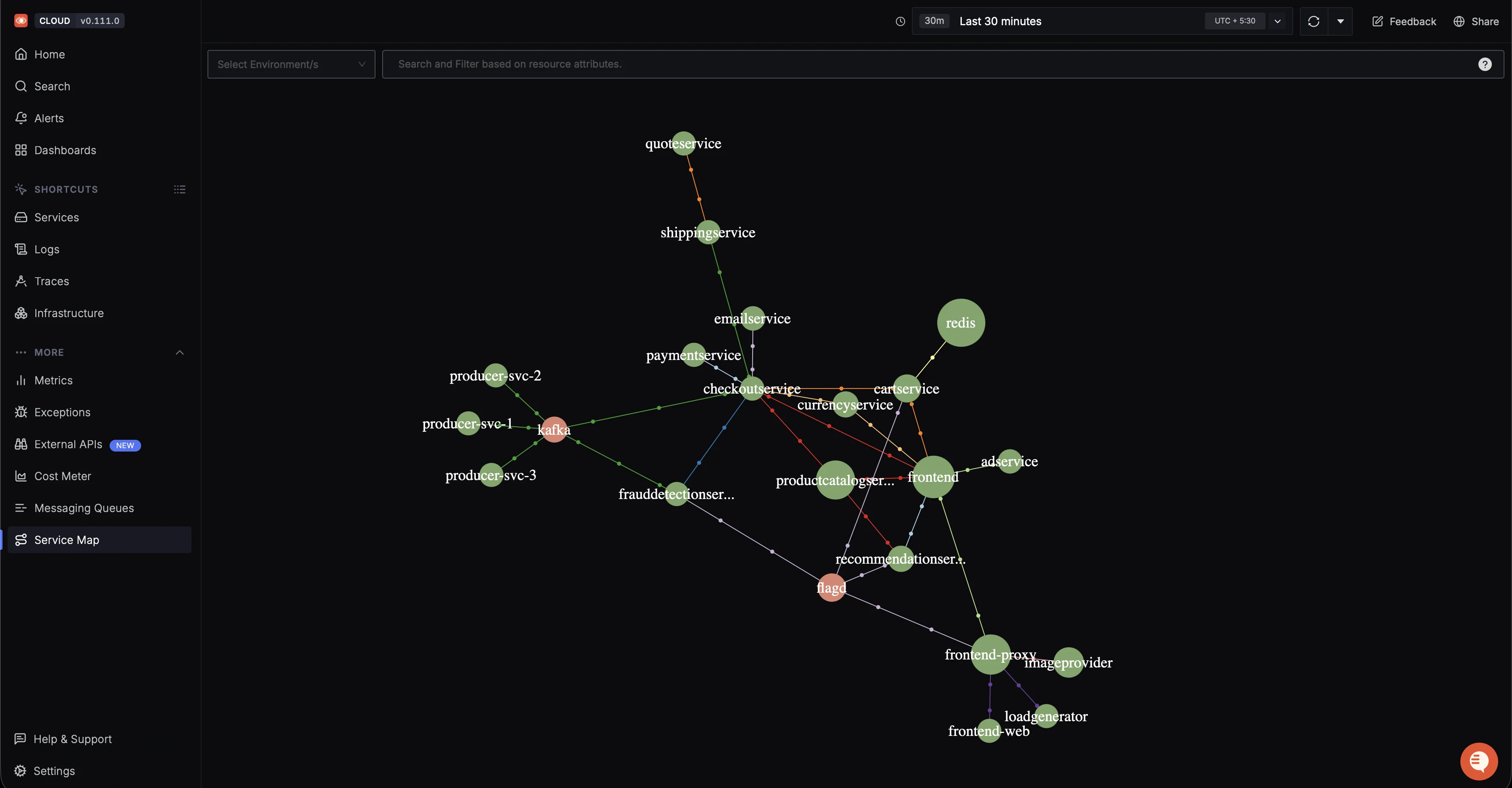

Service maps that automatically generate dependency graphs showing how your containerized services communicate.

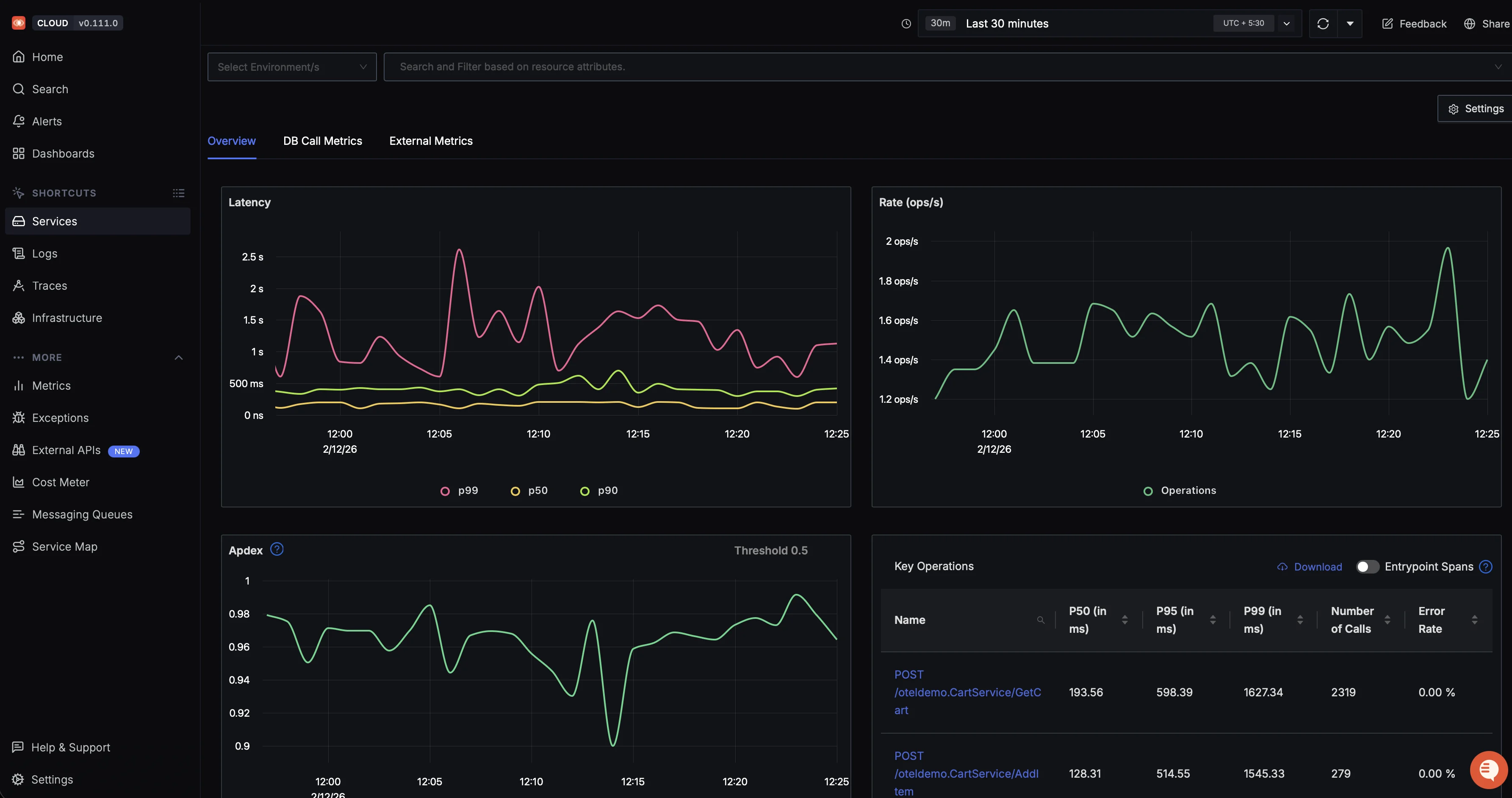

Service map showing request flows, latency, and error hotspots across a microservices-based e-commerce system RED metrics dashboards with out-of-the-box views for request rate, error rate, and latency percentiles per service.

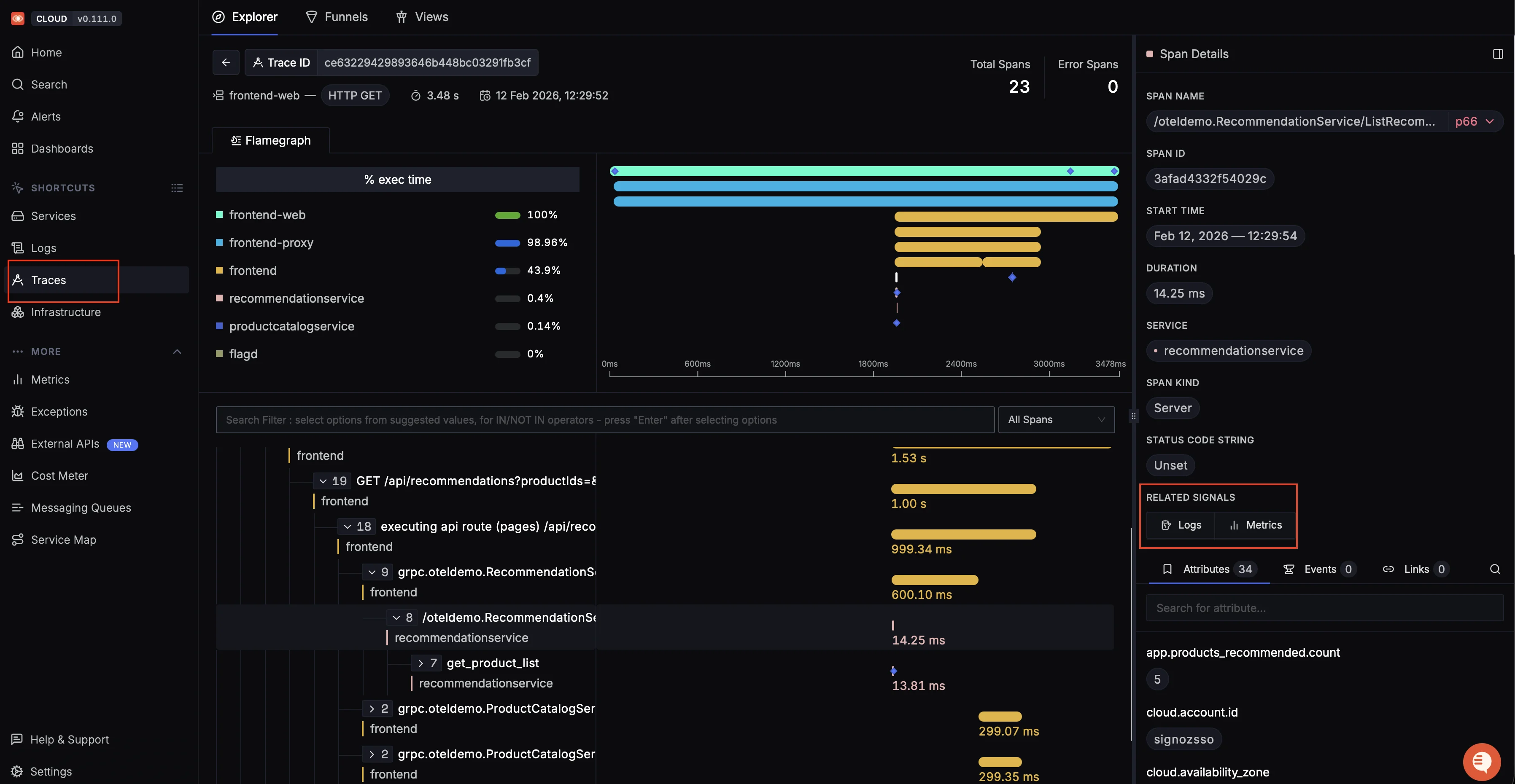

Out of the box dashboard showing latency percentiles, request rate, Apdex score, and key operations for a microservice Trace-to-log correlation that lets you click on a slow trace and jump directly to the logs emitted during that request, filtered by trace ID.

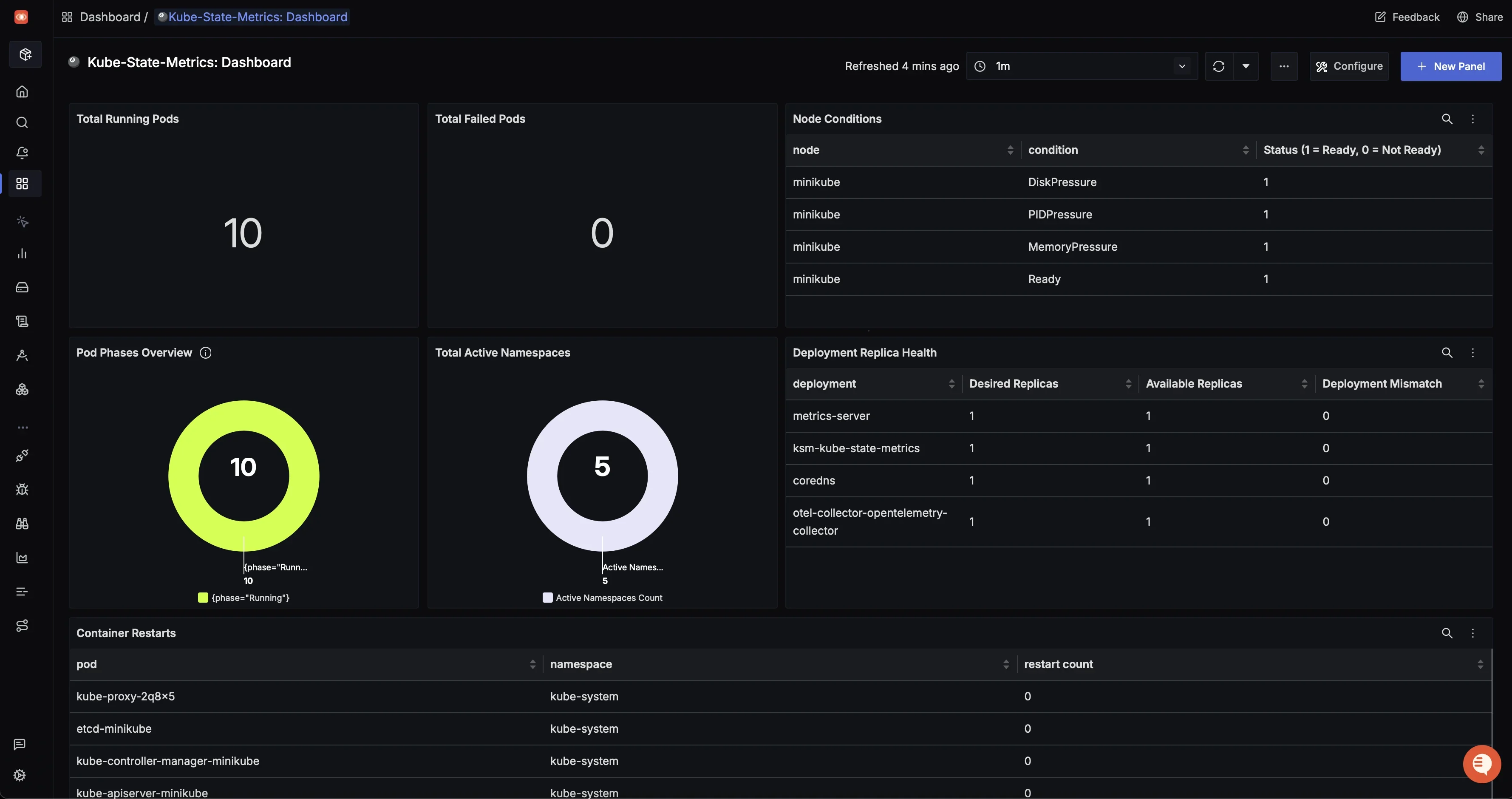

Distributed trace view with flame graph and span timeline, showing how a frontend request flows through multiple services and where time is spent Custom dashboards built using container resource metrics from the

kubeletstatsreceiver to track CPU, memory, and network usage per pod or deployment.

Kube State Metrics Custom Dashboard Alerting on any metric or log pattern, with notifications routed to Slack, PagerDuty, email, or webhooks.

The correlation between signals is where SigNoz saves the most time. When you spot a p99 latency spike on the service overview, you can click through to the specific traces causing it, then jump to the logs from those exact containers during that time window, no context switching between different tools.

Challenges of Container Observability

Ephemeral Containers

Containers can be created and destroyed in seconds, so a container that caused an error might not exist by the time you investigate. Your observability pipeline must export telemetry continuously with minimal buffering delay. This is especially critical for Kubernetes Jobs and CronJobs, where a job might complete before your collector's flush interval, causing logs to be lost entirely.

High Cardinality

Every container and pod gets a unique identifier. Using these as metric labels causes your time-series count to explode. Use labels like deployment, namespace, and service instead of pod_name or container_id for aggregation.

Correlation Across Signals

Scattered tooling slows debugging. OpenTelemetry solves this by attaching consistent resource attributes (service.name, k8s.namespace.name) to all signals. Logs link directly to traces via embedded TraceId and SpanId in LogRecords. Metrics connect differently, they use exemplars to attach a sample trace ID to a datapoint, letting you jump from a metric spike to a representative trace.

Multi-Tenancy and Namespace Isolation

In shared clusters, multiple teams deploy to different namespaces, and each needs visibility into only their own containers. Your observability pipeline must support filtering and access control based on namespace or team labels to enable self-service debugging without noise from other teams.

Best Practices for Container Observability

Use consistent resource attributes

Every telemetry signal (metric, log, span) should carry service.name, deployment.environment, and k8s.namespace.name at minimum. This makes cross-signal correlation possible.

Set resource requests and limits

Without memory limits on your containers, you cannot detect OOM (Out Of Memory) conditions because the OOM killer targets the largest process on the node instead of enforcing per-container limits. Set both requests and limits so Kubernetes can schedule pods correctly, and cgroups enforce memory boundaries.

Sample traces in high-throughput environments

If your services handle thousands of requests per second, collecting every single trace is expensive. Use head-based sampling (decide at the start of the request) or tail-based sampling (decide after the request completes, keeping only errors or slow traces) to reduce volume while retaining useful data.

Do not use high-cardinality labels in metrics

Labels like user_id, request_id, or pod_name create a new time series for every unique value. This causes storage costs and query latency to grow linearly. Use these values in traces and logs instead.

Automate data collection

Use DaemonSets for node-level collection and sidecar injection for application-level instrumentation. Manual setup per container does not scale in environments where pods are created and destroyed automatically.

Set up actionable alerts

Alert on symptoms (high error rate, high latency), not causes (high CPU). High CPU is not a problem if latency is fine. An alert that fires but does not require action is noise and leads to alert fatigue.

FAQs

What tools are used for container observability?

Common tools include Prometheus (metrics), Grafana (visualization), Jaeger (tracing), Fluentd/Fluent Bit (logging), and the OpenTelemetry Collector (unified collection). SigNoz provides all three signals in a single platform with native OpenTelemetry support.

How does OpenTelemetry help with container observability?

OpenTelemetry provides a vendor-neutral standard for instrumenting applications and collecting telemetry data. It supports auto-instrumentation for most languages, meaning you can generate traces, metrics, and logs without changing your application code. The OpenTelemetry Collector acts as a central pipeline for receiving, processing, and exporting data to any compatible backend.

Why is container observability harder than traditional server observability?

Containers are ephemeral, they get created and destroyed frequently, unlike traditional servers that run for months. This means your observability pipeline has to collect data fast enough before containers disappear. Containers also generate high-cardinality metadata (unique pod names, container IDs), and the distributed nature of microservices means that a single request can touch multiple containers, making end-to-end visibility harder without distributed tracing.

What metrics should I monitor for Kubernetes containers?

At minimum, track container_cpu_usage_seconds_total, container_memory_working_set_bytes, container restart counts, and pod status phases for infrastructure health. For application health, track request rate, error rate, and latency percentiles (RED metrics) per service.