Kubelet Logs - Locations, Troubleshooting, and Collection Guide (2026)

The kubelet logs are detailed records of actions performed by the kubelet (a primary agent running on every node in k8s) as it manages pods and containers on a node. These records are produced by the kubelet itself. The logs are useful for troubleshooting failures on your Kubernetes node, as they include details on pod lifecycle events, container operations, health checks, and interactions with the container runtime. The kubelet logs storage location and query commands vary by environment.

Where to Find Kubelet Logs?

Different Kubernetes distributions and infrastructure platforms store kubelet logs in different locations. The following table provides a reference for finding and accessing kubelet logs across common environments.

| Environment | Log Location | Access Command |

|---|---|---|

| Linux (systemd) | systemd journal | journalctl -u kubelet |

| Linux (non-systemd) | /var/log/*.log (exact filename depends on init/package) | sudo grep -i kubelet /var/log/*.log |

| Linux (syslog forwarding enabled) | /var/log/syslog or /var/log/messages depending on distro | sudo grep -i kubelet /var/log/syslog or sudo grep -i kubelet /var/log/messages |

| Minikube (Docker driver) | Inside minikube container | minikube ssh 'journalctl -u kubelet' |

| Minikube (VM driver) | VM filesystem | minikube ssh then journalctl -u kubelet |

| kind | Docker container | docker exec <node> journalctl -u kubelet |

| Amazon EKS | CloudWatch Logs (if enabled via deployed agent like fluent bit) | AWS Console or CLI |

| Google GKE | Cloud Logging | GCP Console or gcloud |

| Azure AKS | Azure Monitor | Portal or az monitor |

| Rancher RKE2 | /var/lib/rancher/rke2/agent/logs/kubelet.log | Direct file access |

| k3s | systemd journal | journalctl -u k3s |

| OpenShift | systemd journal | oc adm node-logs <node> -u kubelet |

How to access Kubelet logs using journalctl?

Modern Linux distributions use systemd to manage the kubelet service. You can access them using the journalctl command, which lets you filter and search logs easily.

For example:

To view the last 100 log entries from the kubelet service, use the following command on the node:

journalctl -u kubelet -n 100You can add a

-fflag to tail the logs.journalctl -u kubelet -fTo filter the logs by time range to focus on specific incidents:

journalctl -u kubelet --since "2024-01-15 10:00:00" --until "2024-01-15 11:00:00"To filter by severity level and see only errors and warnings:

# Errors only journalctl -u kubelet -p err # Warnings + errors (and more severe) journalctl -u kubelet -p warning

Understanding Kubelet log format

Kubelet logs follow a consistent structure. Each log entry captures what the kubelet was doing, when it happened, and where in the code it originated. Once you understand how to read a single line, you can skim large volumes of logs quickly and zero in on the entries that actually explain a failure.

When troubleshooting, read kubelet log lines in this order: severity → message → source → timestamp. Severity tells you what deserves attention first, and the message usually contains the keyword you’ll search for during investigation.

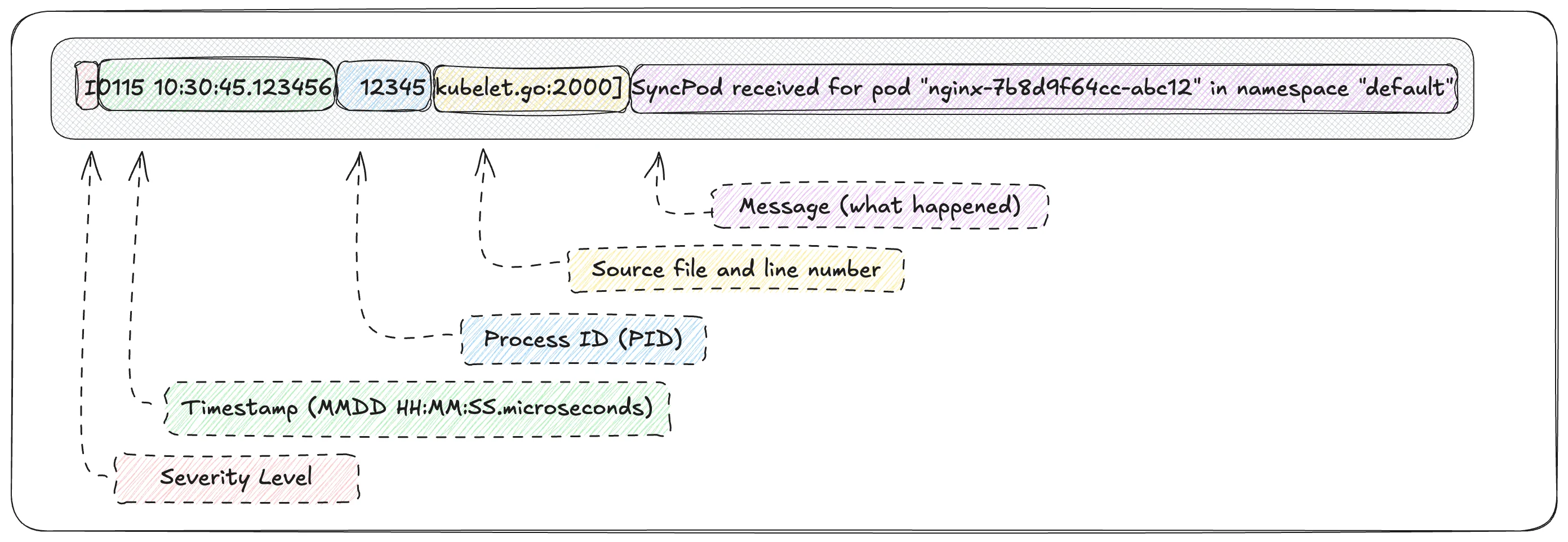

Log Entry Structure

A typical kubelet log entry looks like this:

I0115 10:30:45.123456 12345 kubelet.go:2000] SyncPod received for pod "nginx-7b8d9f64cc-abc12" in namespace "default"

Here’s how to break it down:

- Severity is represented by the first character (

I,W,E,F) and indicates how serious the event is. - Timestamp shows exactly when the event occurred, which is critical when correlating logs with pod events or alerts.

- Process ID identifies the kubelet process that emitted the log.

- Source file and line number point to where in the kubelet codebase the message originated.

- Message describes the action or failure, often including pod names, namespaces, and container identifiers.

In practice, you’ll grep for the message, while severity helps you prioritize which messages matter.

Log Severity Levels

Log severity levels help to prioritize what requires immediate attention.

Info-level messages record normal operations like pod synchronization, container starts, and successful health checks. These form the baseline of expected behaviour.

Warning-level messages indicate potential problems that don't prevent operation but might escalate, such as resource pressure or retry attempts.

Error-level messages signal failures that affect functionality, like failed container starts, image pull failures, or probe failures.

Fatal-level messages are rare and indicate the kubelet itself is crashing.

During an incident, start by filtering for Error and Warning messages around the time the problem occurred, then look at nearby Info messages to understand what the kubelet was attempting just before the failure.

Common Log Patterns to Recognize

Once you can parse individual log lines, the biggest speed-up comes from recognizing recurring phrases that kubelet uses. These patterns appear across most node-level issues and are ideal targets for filtering with journalctl or grep.

| Area | Common phrases to look for | What it usually indicates |

|---|---|---|

| Pod lifecycle | SyncPod received, SyncLoop | Kubelet reconciling desired vs actual pod state |

| Container operations | Container started, Container died, Killing container | Crashes, OOM kills, probe failures, runtime errors |

| Image pulls | Pulling image, Failed to pull image, ImagePullBackOff | Registry auth issues, missing tags, network problems |

| Volume operations | MountVolume, UnmountVolume, failed to mount | CSI issues, permissions, or missing PVCs |

| Health probes | Liveness probe failed, Readiness probe failed | App not responding or probe misconfiguration |

These patterns act as shortcuts: instead of scanning logs blindly, you search for the phrase that matches the symptom you’re seeing.

Here are a few real-world examples you might encounter:

E... Failedto pull image"myapp:v1": rpcerror: unauthorized: authentication required

W... Liveness probe failed: HTTP probe failedwith statuscode:500

E... MountVolume.SetUp failedforvolume"data": permission denied

Each of these lines immediately narrows your investigation to a specific class of problems.

Troubleshooting Common Issues with Kubelet Logs

This section focuses on practical scenarios where kubelet logs become essential during day-to-day Kubernetes operations. It walks through common failure states such as crashing containers, image pull failures, unhealthy nodes, and unschedulable pods, and explains how to correlate pod status, events, and kubelet logs to identify root causes. Each subsection follows a structured troubleshooting flow, showing what to check first, which commands to run, and how kubelet log entries add context beyond what kubectl alone provides.

Diagnosing CrashLoopBackOff

The CrashLoopBackOff status appears when a container repeatedly starts and exits immediately. Kubernetes waits longer after each failed restart instead of restarting the container continuously, which is why you see this specific status rather than continuous restart attempts.

Step 1: Check the pod status and events

Start by examining what Kubernetes reports about the pod:

kubectl describe pod <pod-name>

Look in the Events section for messages like "Back-off restarting failed container" or "Container exited with status X". The exit code provides important clues. Exit code 1 typically indicates an application error, while exit code 137 suggests the container was killed due to memory limits (OOMKilled).

Step 2: Examine container logs

Retrieve logs from the previous container instance before it crashed:

kubectl logs <pod-name> --previous

These logs often reveal the direct cause of the crash, whether an unhandled exception, a missing configuration file, or a failure to connect to a required service.

Step 3: Check kubelet logs for additional context

On the node where the pod is scheduled, examine the kubelet logs for container operation errors:

journalctl -u kubelet | grep <pod-name>

Look for entries containing "Container died", "Killing container", or "Failed to start container." The kubelet logs may show reasons the container logs missed, such as resource limit violations or runtime errors.

Common causes and solutions:

Resource exhaustion is a frequent culprit. When a container exceeds its memory limit, the kernel terminates it with an OOMKilled status. The solution involves either increasing the memory limit or investigating why the application consumes more memory than expected. Liveness probe failures can also trigger CrashLoopBackOff if the probe is misconfigured with an aggressive timeout. Review the probe configuration and consider increasing the initial delay or timeout values.

Resolving ImagePullBackOff

The ImagePullBackOff error indicates that Kubernetes cannot retrieve a container image from its registry. This prevents the container from starting entirely.

Step 1: Verify the image reference

Check that the image name and tag are correct:

kubectl describe pod <pod-name> | grep Image

Typos in image names or tags are surprisingly common. Ensure the full image path matches what exists in the registry.

Step 2: Test image pull manually

SSH to the affected node and attempt to pull the image directly:

crictl pull <image-name:tag>

# or for Docker

docker pull <image-name:tag>

This test helps determine whether the issue is authentication, network connectivity, or the image itself not existing.

Step 3: Check kubelet logs for pull errors

The kubelet logs provide detailed information about image pull attempts:

journalctl -u kubelet | grep -i "pull"

Look for messages containing Failed to pull image, Unauthorized, or Not found. These indicate whether the problem is authentication or image availability.

Common causes and solutions:

For private registries, ensure imagePullSecrets are correctly configured on the pod or service account. Network issues between nodes and registries may require proxy configuration or changes to firewall rules. Rate limiting from public registries like Docker Hub has become increasingly common, and authenticated pulls or local caching can help.

Fixing Node NotReady

When a node enters the NotReady state, the Kubernetes control plane stops scheduling new pods and may begin evicting existing pods. This is one of the most critical issues to resolve quickly.

Step 1: Check node conditions

Examine the node status for specific condition failures:

kubectl describe node <node-name>

Look for conditions like DiskPressure, MemoryPressure, PIDPressure, or NetworkUnavailable. These conditions explain why the node is unhealthy and point to specific resource constraints.

Step 2: Verify the kubelet service status

SSH to the affected node and check if the kubelet service is running:

systemctl status kubelet

If the service has failed or stopped, examine the journal for errors:

journalctl -u kubelet --since "1 hour ago" | grep -i error

Step 3: Check resource utilization

High resource usage can prevent the kubelet from operating correctly:

df -h # Check disk usage

free -m # Check memory

top # Check CPU and process counts

Common causes and solutions:

Disk pressure often results from accumulated container images or log files filling the node's storage. Clearing unused images with crictl rmi --prune or implementing proper log rotation can resolve this. Memory pressure may require evicting low-priority pods or adding more nodes to the cluster. Certificate expiration can also cause NotReady status if automatic rotation has failed.

Debugging Pod Scheduling Failures

When pods remain in a Pending state for extended periods, the scheduler cannot find a suitable node. While the kubelet itself isn't directly responsible, its logs can still provide useful information.

Step 1: Check scheduler events

Examine why the scheduler rejected nodes:

kubectl describe pod <pod-name> | grep -A 10 Events

Look for messages like "Insufficient cpu," "Insufficient memory," "node(s) didn't match node selector," or "node(s) had taint that pod didn't tolerate."

Step 2: Review node kubelet logs for resource reports

The kubelet reports available resources to the control plane. Examine these reports:

journalctl -u kubelet | grep -i "allocatable\|capacity"

These entries show what resources the kubelet advertises as available, which affects scheduling decisions.

From journalctl to Observability: Centralizing Kubelet Logs with OpenTelemetry and SigNoz

Working with kubelet logs usually starts with node-level commands like journalctl -u kubelet or tailing /var/log/*.log (exact path depends on your distro and kubelet/service configuration). This works for debugging a single node, but it quickly breaks down when you need to compare behaviour across nodes, investigate intermittent pod failures, or correlate kubelet errors with cluster-wide issues.

OpenTelemetry (OTel) helps by standardizing how kubelet logs are collected and shipped off from the node. An OpenTelemetry Collector running as a DaemonSet can read kubelet logs directly from systemd (journald) or log files, enrich them with Kubernetes metadata (node name, cluster, region), and forward them to a central backend without vendor lock-in.

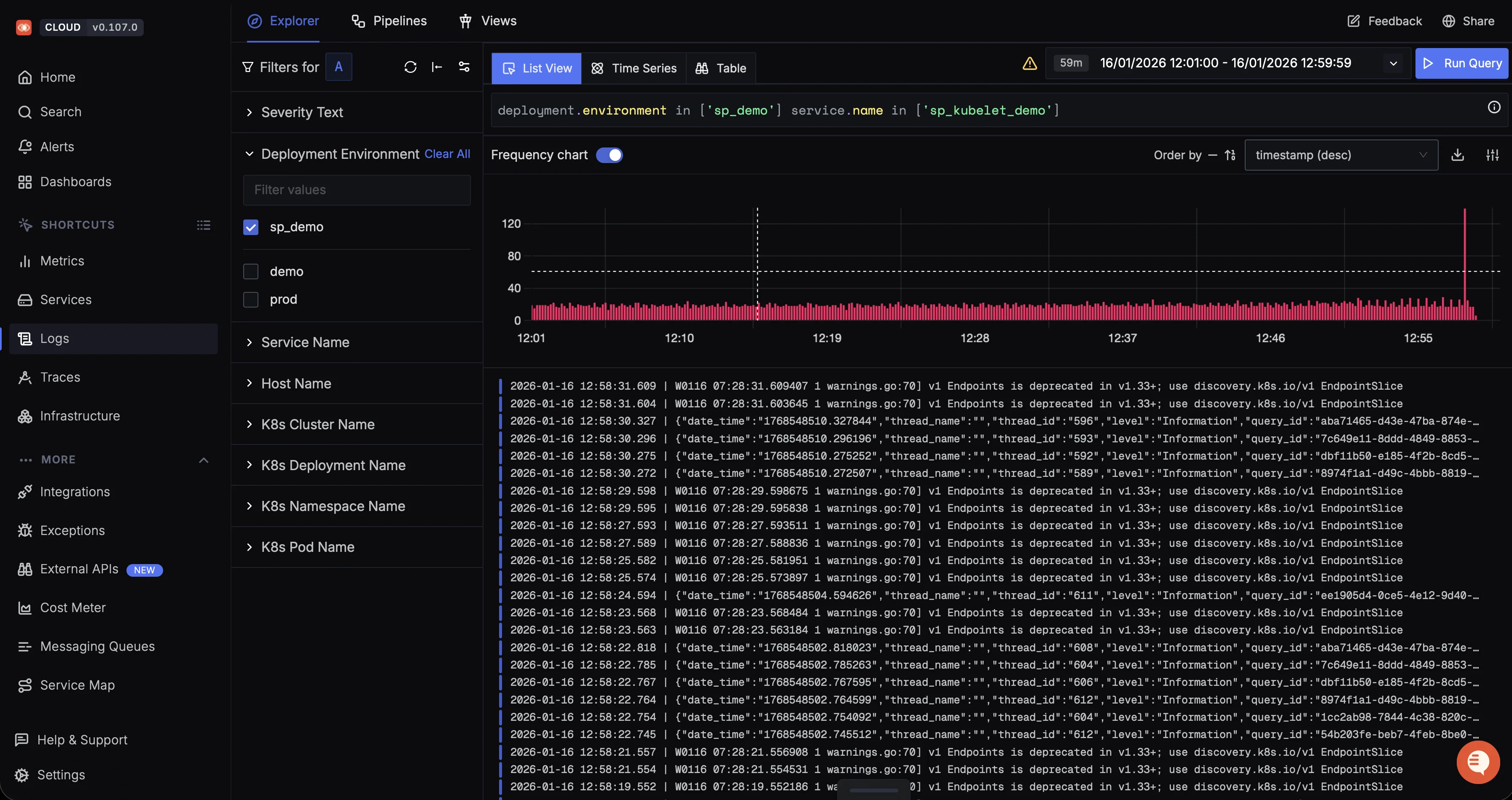

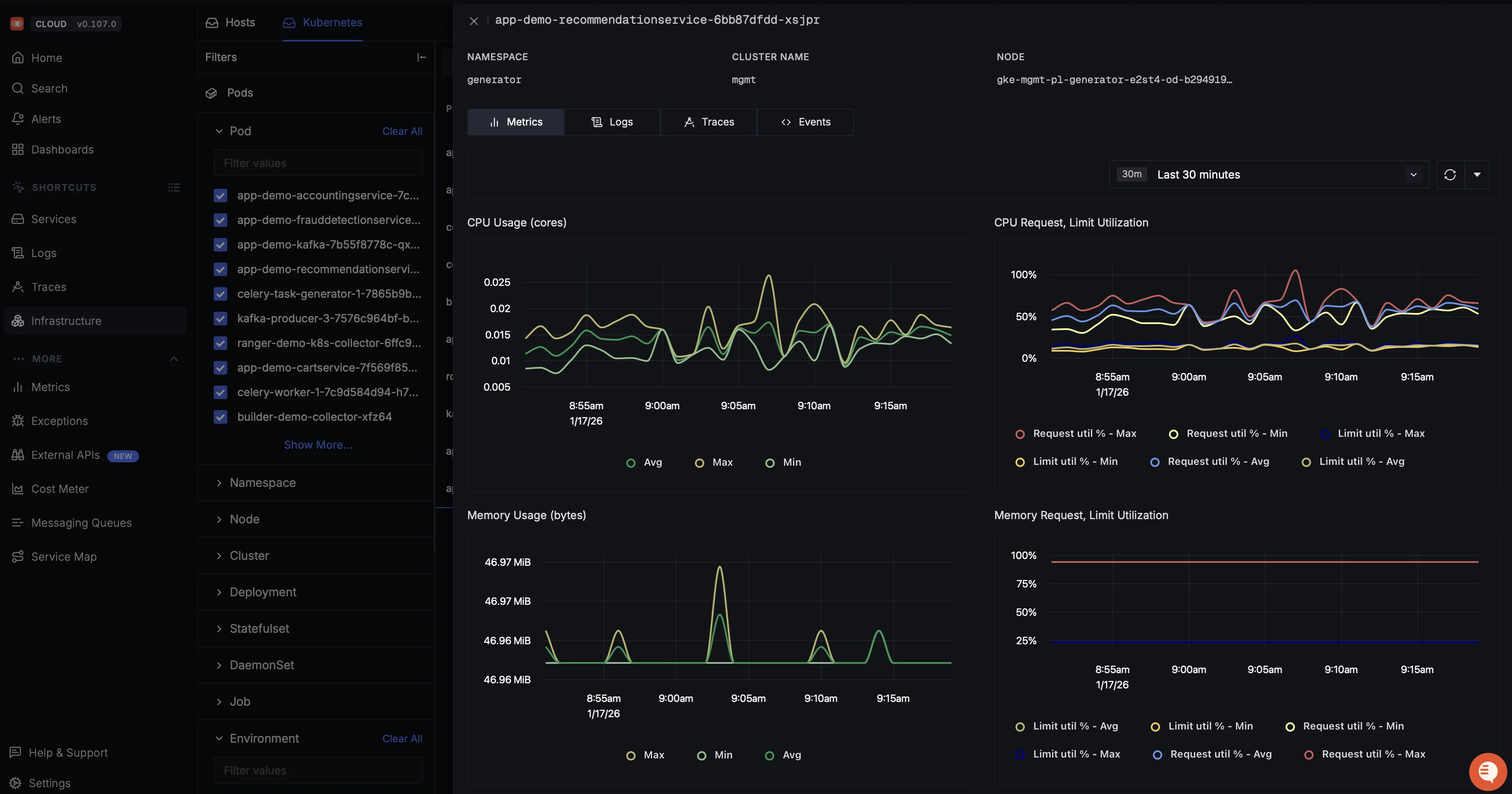

SigNoz, as an OpenTelemetry-native observability platform, lets you search, filter, and correlate kubelet logs across all nodes from a single place. You can quickly slice kubelet errors by node or time range, line them up with node and pod metrics, and retain logs even when nodes are recycled.

This turns kubelet logging from ad-hoc journalctl sessions into centralized logging that scales with your cluster.

SigNoz also provides you with log based alerts. Using these alerts, you can define queries on kubelet logs such as spikes in Warning or Error entries, repeated FailedProbe messages, or frequent NotReady node transitions and SigNoz will continuously evaluate those conditions in the background. When the threshold is breached, SigNoz sends notifications to your preferred channels (Slack, PagerDuty, email, etc.), so you don’t have to manually watch journalctl to know when kubelet behaviour starts to degrade. Learn more in the SigNoz alerting documentation.

Best Practices for Production

Effectively operating kubelet logging in production requires attention to several key areas.

Log Rotation and Retention

The kubelet includes built-in log rotation for container logs, configured through the containerLogMaxSize and containerLogMaxFiles parameters. Setting containerLogMaxSize to 10Mi means log files rotate when they reach 10 megabytes. The containerLogMaxFiles parameter controls how many rotated files to keep. Without proper configuration, logs can consume all available disk space and trigger DiskPressure conditions.

For the kubelet's systemd-managed logs, the journal automatically rotates them based on system-wide settings. Configure /etc/systemd/journald.conf to specify maximum disk usage and retention policies appropriate for your environment.

Metadata Enrichment

Enrich logs with contextual information as they are collected. When the OpenTelemetry Collector processes log entries, it can add Kubernetes metadata, including labels and annotations attached to pods. This enrichment turns raw log lines into records that already include namespace, pod, and container info, so they’re much easier to query and correlate.

Monitoring Log Infrastructure

Log infrastructure requires its own monitoring. Track disk usage on nodes to ensure logs aren't consuming excessive space. Monitor the log collection agents themselves for processing rates, buffer utilization, and error counts. If logs stop flowing from a node, you need to know immediately.

Further Reading

For more information on Kubernetes logging and observability, explore these related resources: