What is OOM (Out of Memory)? How to detect and debug

An Out of Memory (OOM) state occurs when the environment (might be the operating system, container, or application runtime) attempts to allocate memory but none is available. When this happens, the system must take drastic action to keep running, often resulting in a crash or the termination of a process.

How does OOM Manifest?

OOM happens because modern systems rely on Virtual Memory, an abstraction that provides software with a contiguous block of memory that may not physically exist. This decoupling allows the operating system to practice overcommitment, promising more memory to processes than is actually installed on the machine. The OS assumes that applications will not simultaneously use their full allocation.

However, when this gamble fails, and processes try to consume their reserved space all at once, the system faces a hard constraint. Unable to manufacture more RAM, the OS must reclaim resources to survive, usually by terminating a process.

This article explains the mechanics of OOM across these different environments. We will look at why it happens, how the system decides what to kill, and how you can debug and prevent it.

1. OOM in Linux (Linux OOM Killer)

On a standard Linux server, the kernel prioritizes its own survival above all else. If the system runs critically low on memory, the kernel invokes a mechanism known as the OOM Killer (oom_killer).

How It Works

The OOM Killer is not random. It uses a calculation method to select a victim process to terminate. The goal is to free up the maximum amount of memory while causing the least amount of system damage.

The kernel assigns every running process an oom_score, which you can view in /proc/<pid>/oom_score. The score ranges from 0 to 1000.

- Higher score: The process is using a lot of memory and is a prime target.

- Lower score: The process is small or critical (like

sshd) and should be spared.

When the limit is hit, the kernel sends a SIGKILL (Signal 9) to the process with the highest score. This signal cannot be caught or ignored. The process stops immediately.

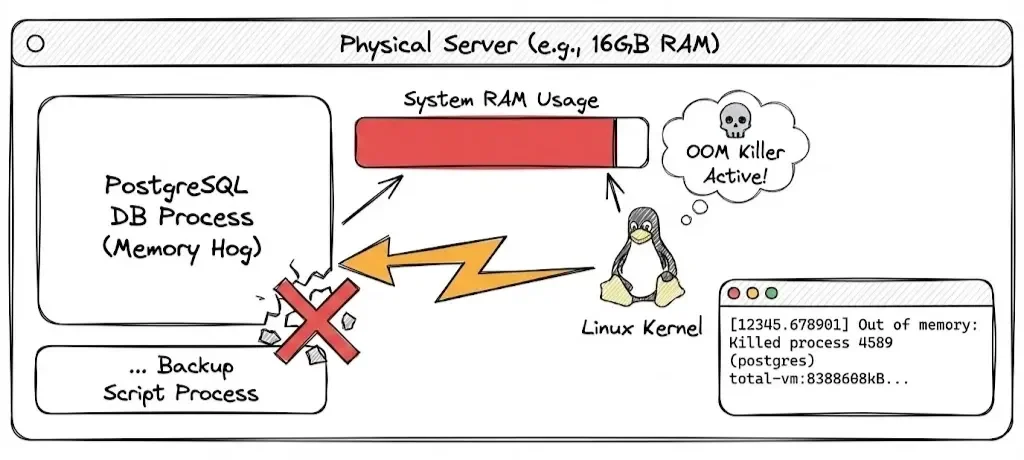

Linux OOM Killer Example

You have a linux server running a database (like PostgreSQL), and a backup script starts running at the same time. The physical RAM fills up completely. The OS kernel steps in to save the system.

You usually find out about a Linux OOM event after the kernel has already terminated a process to reclaim memory. The server might have gone quiet for a minute, or a database service suddenly restarted. The evidence lies in the system logs.

What you see in the logs (dmesg or /var/log/syslog):

[12345.678901] Out of memory: Killed process 4589 (postgres) total-vm:8388608kB, anon-rss:4194304kB, file-rss:0kB

Explanation:

Killed process 4589 (postgres): The kernel calculated that killing the Postgres process would free up the most memory, saving the OS, even though it was the most critical application.total-vm: Indicates the amount of virtual memory the process was using at the time of death.

Fixing OOM in Linux

If the killed process was the actual memory hog (high anon-rss), you need to tune its configuration (e.g., reducing shared_buffers in Postgres) or upgrade the server's RAM.

However, sometimes the victim is innocent. If a backup script runs and eats all available RAM, the OOM Killer might sacrifice your web server simply because it was the largest available target. In this case, you can adjust the badness score of critical services to protect them.

You can lower a process's likelihood of being killed by writing a negative value to /proc/<pid>/oom_score_adj.

For example, writing -1000 essentially grants the process immunity from the OOM Killer. The oom_score_adj score ranges from -1000 to +1000.

2. Kubernetes and OOMKilled (Exit Code 137)

In Kubernetes, OOM events are heavily influenced by Cgroups (Control Groups). Cgroups allow Kubernetes to set strict memory limits for a specific container, regardless of the node's available RAM.

Kubernetes OOM Example - Understanding the Limits

When you define a pod, you typically set resource requests and limits:

resources:

limits:

memory: "512Mi"

requests:

memory: "256Mi"

If your container tries to use 513MiB, the underlying container runtime (containerd or Docker) sees this violation of the Cgroup limit and kills the container. Kubernetes reports this as:

- Status:

OOMKilled - Exit Code:

137

The exit code 137 is significant. It is calculated as $128 + 9$, where 9 represents SIGKILL. This confirms the container didn't crash due to a bug. It was deliberately shot down for exceeding its allowance.

Debugging OOM in Kubernetes

First, let’s confirm the exit code:

kubectl describe pod <pod-name>

Look for the Last State section.

Last State:

Terminated:

Reason: OOMKilled

Exit Code: 137

Next, compare the limit to your application's actual usage. A common mistake is checking container_memory_usage_bytes and seeing a value lower than the limit. This happens because Kubernetes uses Working Set memory to make eviction decisions, not just RSS.

Working Set includes resident memory plus some types of cached memory that the kernel cannot easily evict. The container_memory_working_set_bytes is the metric that best approximates what the OOM killer cares about, watch it as it approaches your limit, and once the limit hits, the process is killed.

Fixing OOM in Kubernetes

Right-size the limit: If your app normally uses 450MiB and your limit is 512MiB, you have very little headroom for traffic spikes. Increase the limit by 20-30%.

Check for leaks: If increasing the limit from 1GiB to 2GiB still crashes, you likely have a memory leak in the application code.

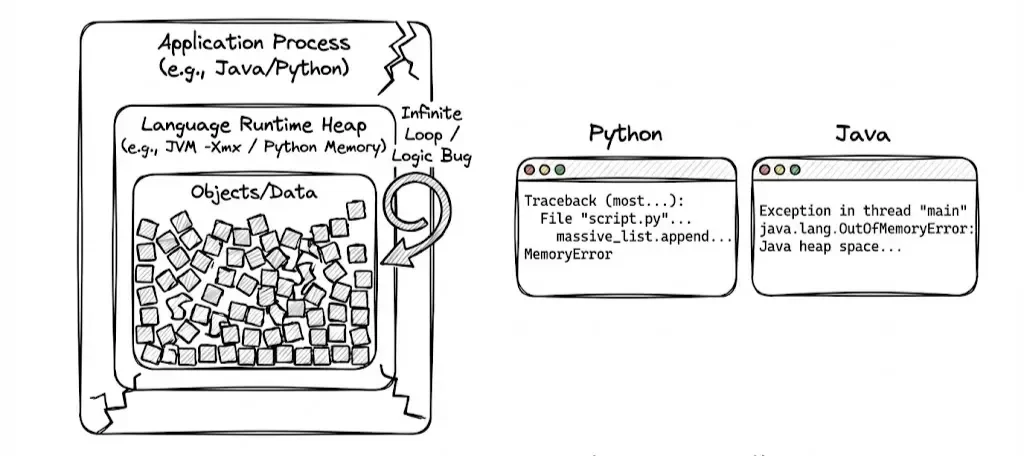

3. Application Runtime OOM (Java & Python)

Application exhausts it’s own internal memory allocation

Sometimes, the operating system and the container are fine, but the application crashes internally. This happens when the language runtime has its own memory limits.

Java: java.lang.OutOfMemoryError

The Java Virtual Machine (JVM) pre-allocates a heap based on the -Xmx flag. If your code creates more objects than can fit in this heap, the JVM throws an error and crashes. The OS sees this as a normal program exit (often Exit Code 1), not an OOM Kill.

Common causes:

Java heap space: You are holding onto too many objects (e.g., a static list that never gets cleared).GC overhead limit exceeded: The garbage collector is running constantly but freeing almost no space.Metaspace: You are loading too many classes or using a framework that generates dynamic proxies.

Debugging: You need a Heap Dump. This is a snapshot of memory at the moment of the crash. Configure your JVM to generate this automatically:

-XX:+HeapDumpOnOutOfMemoryError -XX:HeapDumpPath=/var/logs/

Load the resulting .hprof file into a tool like Eclipse MAT or VisualVM. Look for the "Dominator Tree" to see which objects are consuming the most memory.

Python: MemoryError

Python raises a MemoryError , when an operation runs out of memory. This often happens in data science workloads (e.g., Pandas) when loading a dataset that is larger than available RAM.

# Example: Creating a list that exceeds RAM

massive_list = []

while True:

massive_list.append(' ' * 10**7)

# Result: MemoryError

Debugging: Python does not dump memory by default. For local debugging, you can use the built-in tracemalloc module to find the lines of code allocating the most memory.

import tracemalloc

tracemalloc.start()

# ... run your code ...

snapshot = tracemalloc.take_snapshot()

top_stats = snapshot.statistics('line_no')

print("[ Top 10 ]")

for stat in top_stats[:10]:

print(stat)

How to avoid OOM proactively

OOM is not a sudden event. It is the last stage of sustained memory pressure. Waiting for a crash to fix OOM is stressful. A better approach is to monitor your memory usage trends and get alerted before you hit the wall.

This is where OpenTelemetry (OTel) and SigNoz provide value. Together, they help you detect memory pressure early, correlate signals across layers, and act before the kill signal is ever sent.

Preventing OOM comes down to three principles:

- Collect & Visualize the right memory metrics

- Correlate memory behaviour across layers

- Alert on trends, not failures

Let’s walk through a hands-on example where we intentionally trigger an OOM crash to demonstrate detection, monitoring, and alerting using OpenTelemetry and SigNoz.

For the sake of this hands-on, we’ll use a Python application that gradually allocates memory until it raises a MemoryError while exporting traces, logs, and metrics via OTLP. This gives you a clean, controlled OOM ramp that SigNoz can visualize, correlate, and generate alert.

Step 1: Clone the GitHub Repository

Clone the Python OOM Demo App GitHub repository & change directory to oom demo application

git clone https://github.com/SigNoz/examples.git

cd examples/python/python-oom-demo/

Step 2: Install the requirements.txt file

Install the required libraries for the Python application to run

pip install -r requirements.txt

Step 3: Configure Environment Variables

To configure OpenTelemetry for your application, export the necessary environment variables. These variables define the data export settings and identify your application in SigNoz.

Run the below in your terminal:

export OTEL_EXPORTER_OTLP_ENDPOINT="https://ingest.<REGION>.signoz.cloud:443"

export OTEL_EXPORTER_OTLP_HEADERS="signoz-ingestion-key=<YOUR-Ingestion-KEY>"

export OTEL_EXPORTER_OTLP_PROTOCOL="grpc"

export OTEL_SERVICE_NAME="python-oom-demo"

Be sure to replace <SIGNOZ_INGESTION_KEY> with your actual SigNoz ingestion key and <REGION>. If you haven't created one yet, you can follow Generate Ingestion Key to generate your access key.

Step 4: Start the Python application

After setting the environment variables, start your application.

python app.py

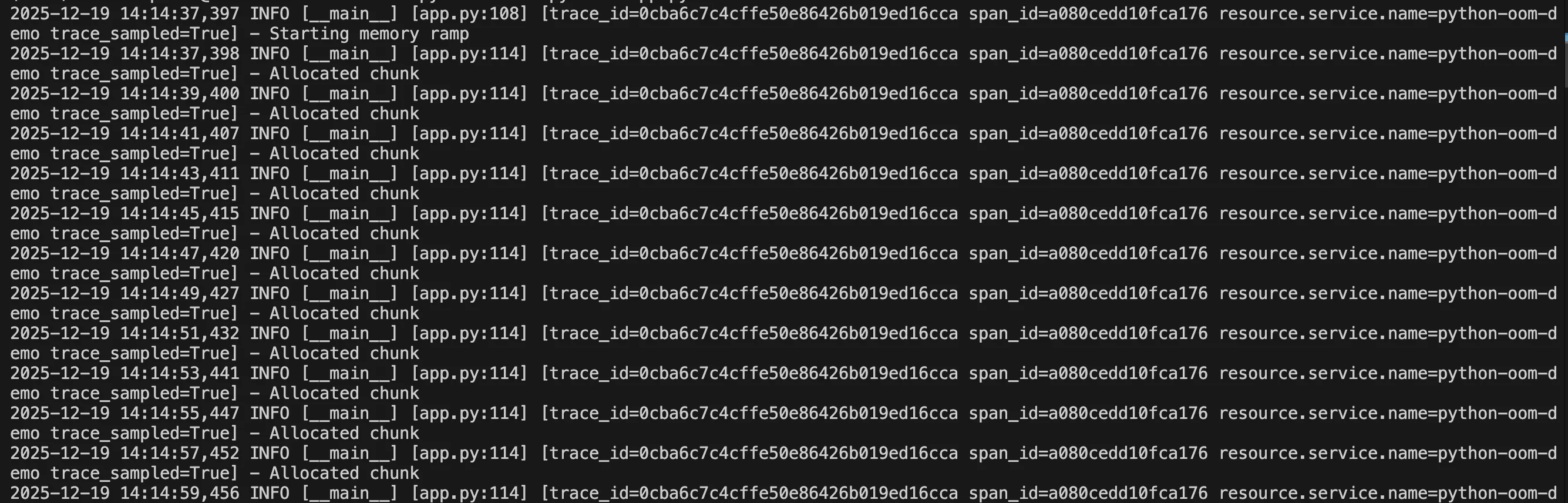

You should be able to see memory getting allocated in chunks of 10 mb per 2 seconds.

Step 5: Visualize, Monitor and Setup Alerting in SigNoz

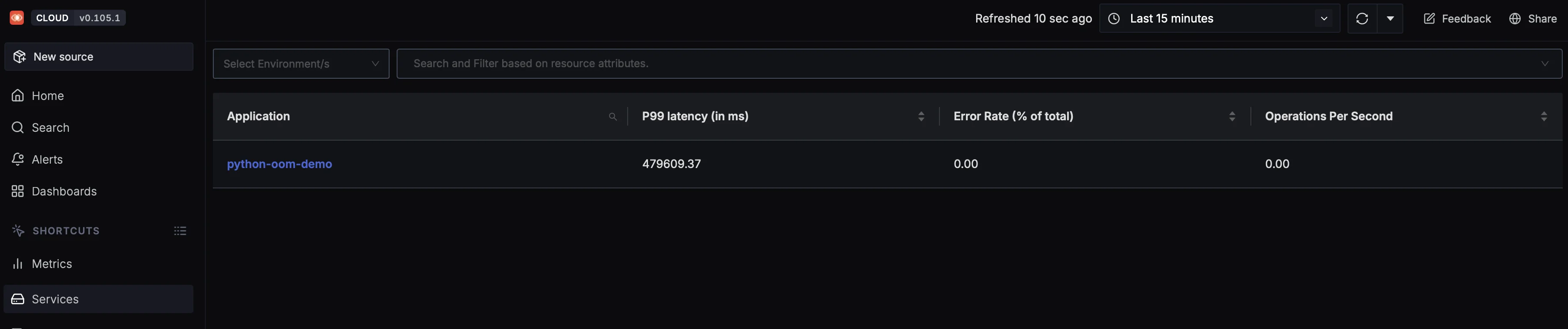

Once your application is running and has generated some load, you can begin monitoring it in your SigNoz Cloud account. Navigate to the Services tab, where your application should appear automatically.

To visualize memory consumption over time, create a custom metric panel. Navigate to Metrics → Explore, select the metric process.memory.rss, and filter by your service name.

This metric represents the resident memory used by the process.

You can also configure an alert on this metric to proactively detect memory pressure. Follow the SigNoz Alert Setup Guide to trigger alerts when memory crosses a defined threshold.

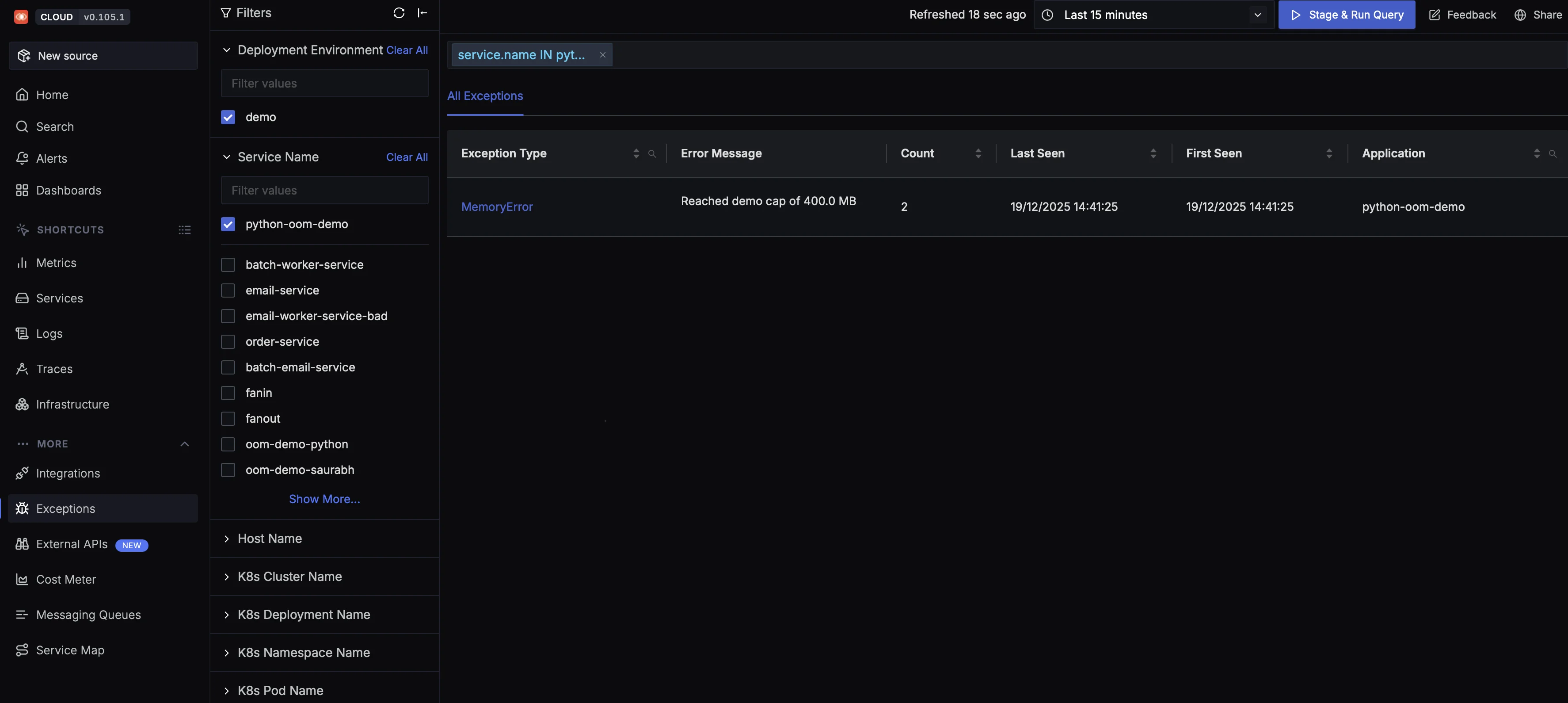

Once the application reaches the maximum available memory, it crashes. This failure is captured as an exception in SigNoz. Navigate to the Exceptions tab and filter by your service name.

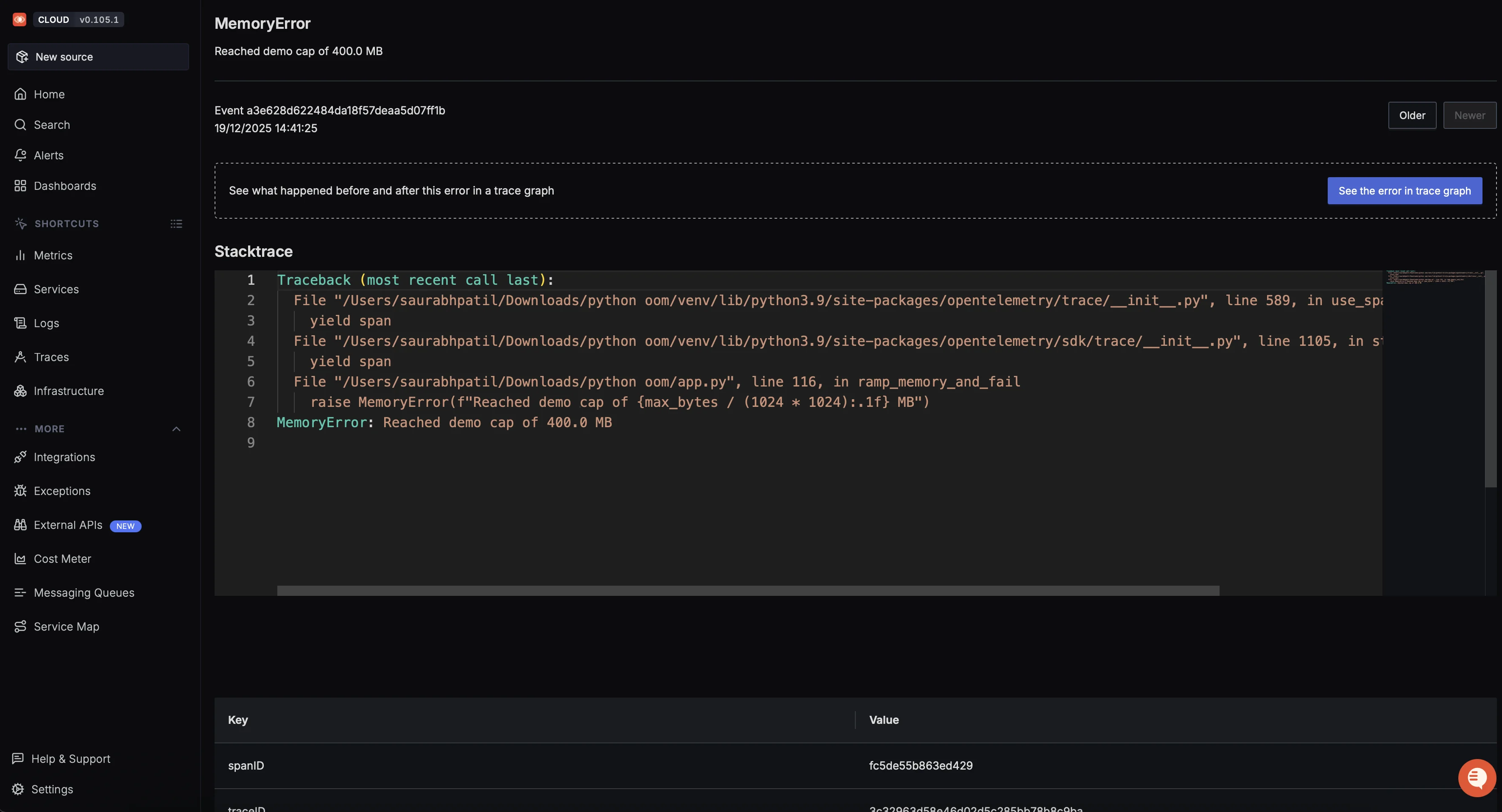

Click on the MemoryError entry to drill down into details such as the stack trace and correlated traces. SigNoz lets you analyze what happened before and after the failure using trace context.

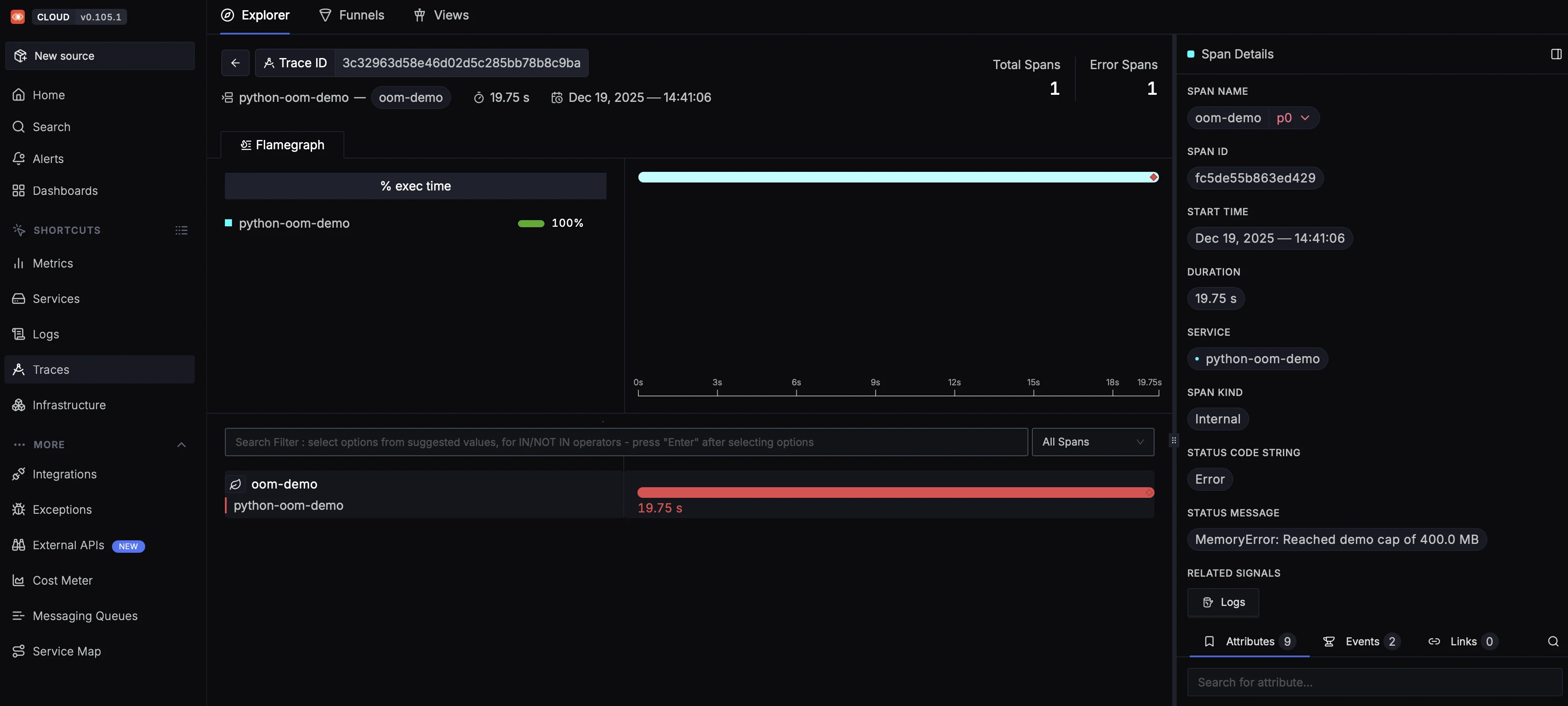

You can further explore the execution path by clicking “See the error in trace graph”, which opens the distributed trace view.

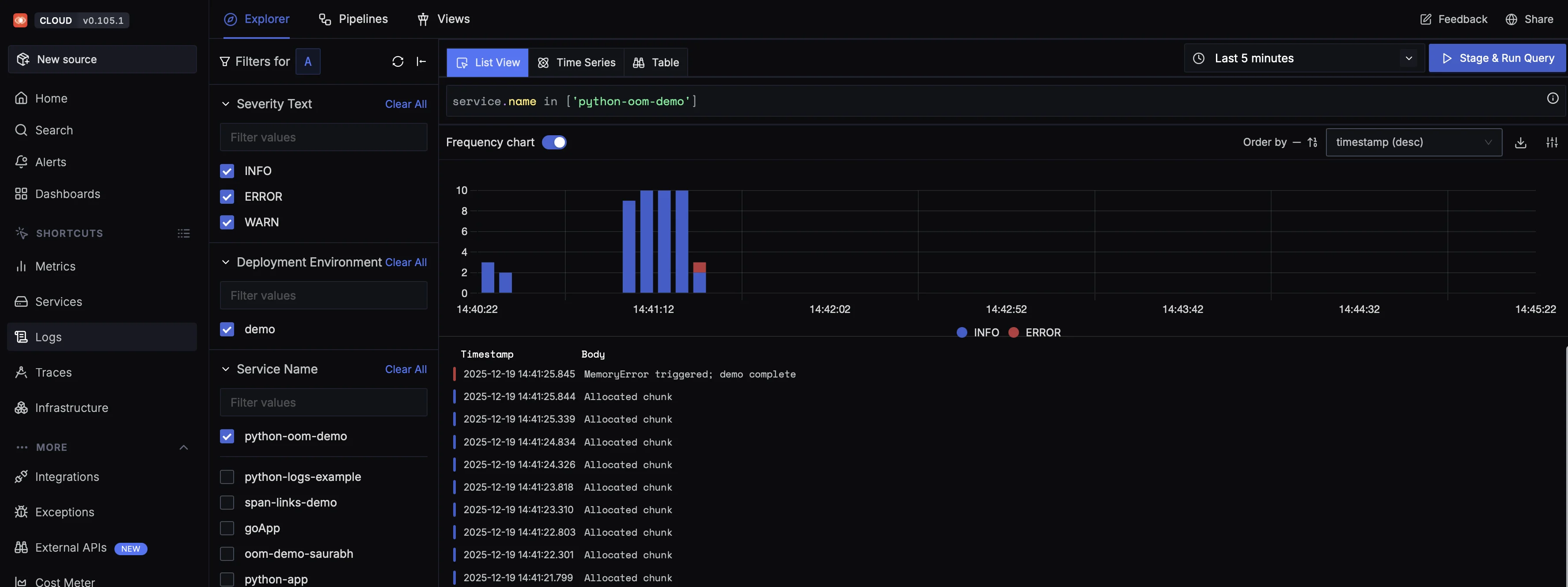

From the trace, you can seamlessly pivot to logs to understand what the application was doing at that moment.

This log timeline shows the exact sequence that led to the OOM crash. Repeated Allocated chunk entries indicate sustained memory growth, followed by a terminal MemoryError when the process exceeds its limit.

When correlated with metrics and traces, this gives you a complete picture: metrics show memory steadily rising, logs explain what the application was doing, and traces pinpoint where the failure occurred.

This example demonstrates how OOM develops gradually and how memory pressure becomes visible long before a crash occurs. By correlating memory metrics with logs and traces, SigNoz helps you understand not just that an OOM happened, but why it happened and where it originated.

We hope this guide answered your questions about what OOM is, how to detect and troubleshoot it across different environments, and how to proactively prevent it in production.

You can also subscribe to our newsletter for insights from observability nerds at SigNoz, get open source, OpenTelemetry, and devtool building stories straight to your inbox.