What are Kubernetes Pods? Not Just a Container Wrapper

A Pod is the smallest deployable unit in Kubernetes. Your application code is packaged in a container, Kubernetes runs Pods, and these containers reside in them. Mostly, a Pod contains a single container, which can make it feel like an unnecessary abstraction. If containers already package applications, why add another layer? The answer lies in how Kubernetes runs and manages applications at scale. Pods give Kubernetes a consistent unit for placing, running, and managing containers.

Let’s start by understanding what a Pod actually is.

What is a Kubernetes Pod?

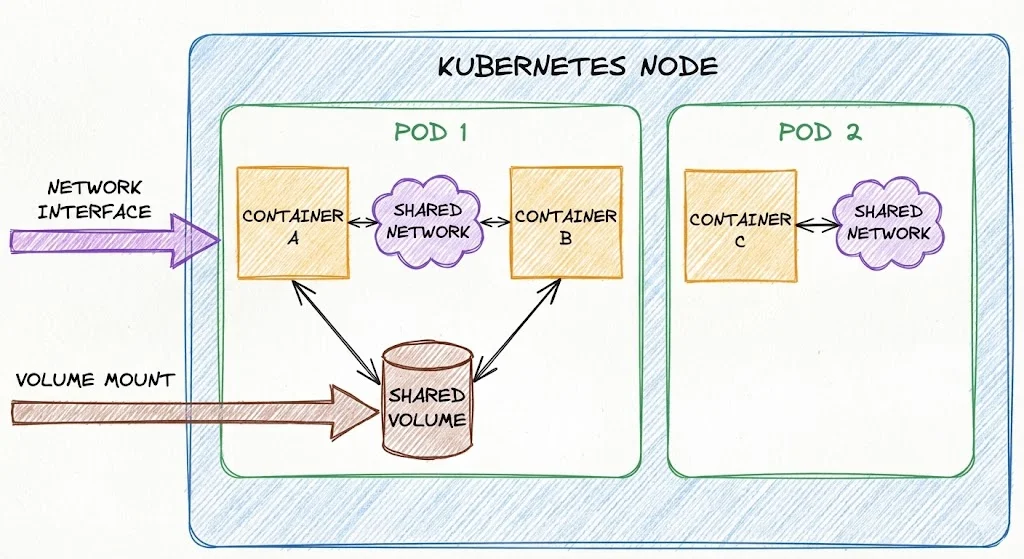

A Pod is a logical host for one or more containers. When you create a Pod, you are creating an environment where containers run. This environment provides critical shared resources to the containers inside it:

Shared Network Namespace: Every Pod gets a unique IP address in the cluster. All containers within a Pod share the same IP address and network namespace, allowing them to communicate via localhost.Shared Volume: You can specify Volumes that all containers in the Pod can access to read and write data.

You cannot run a container in Kubernetes without a Pod. If you run two tightly coupled programs, a web server and a background process that updates the server's content as only containers, Kubernetes might place the web server on Node A and the background process on Node B, which would separate the containers across different nodes and make communication slow and complex.

By using Pods, Kubernetes make sure that these tightly coupled containers always run together on the same machine. They start together, stop together, and share the same environment.

Pod vs Container vs Node

Containers, Pods, and Nodes represent different levels of abstraction in Kubernetes.

A Container (for example, a Docker container) is simply an application process with its dependencies. It knows nothing about clusters, scheduling, or other containers.

A Pod is the smallest unit that Kubernetes schedules. It acts as a logical host that groups one or more containers, providing them with a shared network address and shared storage. Kubernetes schedules Pods onto machines.

A Node is the machine, virtual or physical, that provides CPU, memory, and networking resources.

Nodes run Pods, and Pods run containers. The differences become clearer when you compare them side by side.

| Aspect | Docker (Container) | Kubernetes Pod | Node |

|---|---|---|---|

| What it is | An application process | A wrapper around one or more containers | A machine (VM or physical) |

| Layer | Process | Logical host | Infrastructure |

| Who schedules it | You / Docker | Kubernetes | Cluster admin / cloud |

| Networking | Each container gets its own network namespace | Single IP shared by all containers in the Pod | Has a node-level IP |

| Purpose | Run an app | Run containers together | Provide resources |

| Failure handling | Restart container | Recreate Pod | Replace node |

Core Characteristics of a Kubernetes Pod

A Kubernetes Pod acts like a logical host for one or more containers. Regardless of how many containers it runs, a Pod always provides these core characteristics:

- Shared Network: All containers in a Pod run in the same network namespace and are assigned a single Pod IP. They can communicate directly over

localhostwithout service discovery. - Shared Storage: Containers can mount the same volumes, allowing them to exchange files, sockets, or logs through the filesystem.

- Shared Lifecycle: Kubernetes makes scheduling decisions at the Pod level. Containers inside a Pod are scheduled, started, stopped, and restarted together.

- Shared Context: Metadata, environment variables, ConfigMaps, Secrets, and CPU/memory requests and limits are defined at the Pod level, and the containers within it inherit them.

This model makes Pods ideal for running tightly coupled helpers, such as sidecars, proxies, or log shippers, alongside the main application container.

Types of Kubernetes Pods

Kubernetes Pods are commonly categorized by their structure and usage. These usage patterns are what we commonly refer to as Pod types.

- Single-Container Pods: A single-container Pod runs exactly one container and is the most common Pod model in Kubernetes. It is used for most stateless workloads, such as web servers, APIs, and workers, and should be the default choice unless multiple containers must be tightly coupled.

- Multi-Container Pods: A multi-container Pod runs multiple containers that share the same network namespace and storage volumes. These Pods are used when containers must run together and communicate over

localhost. Common patterns include sidecars for logging or metrics, ambassadors for proxying external services, and adapters for transforming application output. - Pods with Init Containers: Init containers run before the main application containers and must succeed for the Pod to start. They are used for setup tasks such as dependency checks, configuration generation, or database migrations.

- Static Pods: Static Pods are managed directly by the kubelet and defined on the node’s filesystem rather than through the API server. They are primarily used for Kubernetes control plane components and are not managed by standard controllers.

- Ephemeral: Ephemeral Pods are short-lived Pods created for temporary tasks rather than long-running services. They are commonly used by Jobs and CronJobs to run batch workloads that terminate once the task completes.

- Controller-Managed Pods: In production, Pods are typically created and managed by controllers such as Deployments, StatefulSets, and DaemonSets. These controllers handle scaling, restarts, and rescheduling, making direct Pod management unnecessary.

Multi-Container Pod Patterns

Most Pods run only a single container. However, the "wrapper" nature of Pods allows for specific patterns where multiple containers work together.

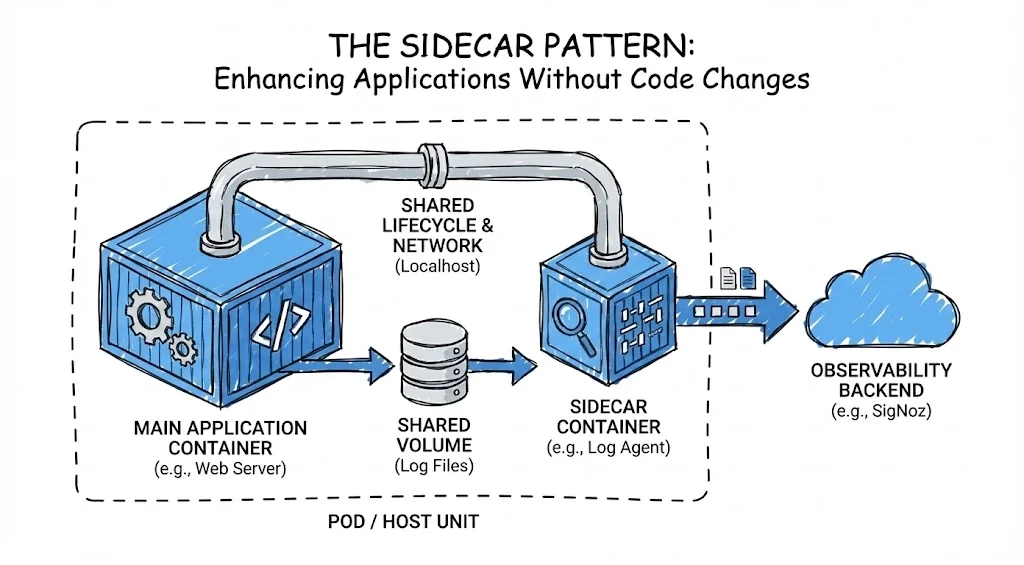

The Sidecar Pattern

A sidecar is a helper container that enhances the main application without changing its code.

- Example: Your main container runs a web server. A sidecar container runs a log agent that reads the server's log files and ships them to an observability backend like SigNoz.

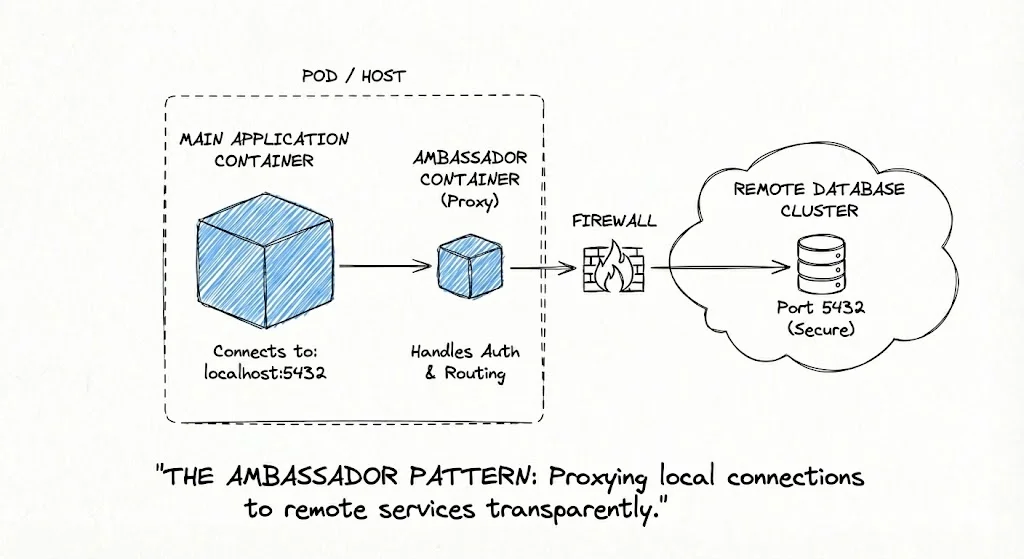

The Ambassador Pattern

An ambassador container acts as a proxy for the main container, abstracting away complex networking and external communication logic.

- Example: Your application connects to

localhost:5432for a database. The ambassador proxies that connection to the correct remote database cluster, handling authentication and routing automatically.

How Kubernetes Tracks and Maintains Pod Health

Kubernetes determines whether an application is healthy by observing the Pod lifecycle and continuously evaluating health probes. These signals decide when containers are started, restarted, or removed from service.

The Pod Lifecycle

Pods are created, assigned a unique ID, scheduled to a node, and run until they complete or are terminated. If a Pod fails or the underlying Node dies, the Pod is not "resurrected." Ideally, a controller (like a Deployment) replaces it with a new, identical Pod.

The pod lifecycle is as follows:

Pending: The API server has accepted the Pod, but it is not running yet. This usually means the scheduler is finding a node, or the container image is downloading.Running: The Pod is bound to a node, and at least one container is running or restarting.Succeeded: All containers in the Pod terminated successfully (exit code 0) and will not restart.Failed: All containers terminated, and at least one failed (non-zero exit code).Unknown: The control plane cannot communicate with the Pod's Node.

Health Probes

Just because a Pod's state is "Running" doesn't mean your application is working. Kubernetes uses three types of probes to check the actual health of your containers:

- Liveness Probe: Checks if the application is alive. If this fails, Kubernetes kills and restarts the container.

- Readiness Probe: Checks if the application is ready to accept traffic. If this fails, Kubernetes stops sending network traffic to the Pod until it passes.

- Startup Probe: Used for legacy applications that take a long time to start. It pauses the other probes until the app is fully initialized.

Working with Pods Using kubectl

Let's do a quick hands-on exercise where you'll learn how to deploy a simple Pod, inspect its details, view logs, exec into it, and finally clean it up.

Step 1: Create a demo-pod.yaml

Kubernetes resources are defined using YAML manifests. Create a file named demo-pod.yaml and paste the following configuration:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: demo-pod

spec:

containers:

- name: app

image: nginx

ports:

- containerPort: 80

Step 2: Create the pod

Apply the YAML file to create the Pod:

kubectl apply -f demo-pod.yaml

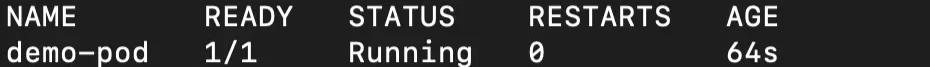

Step 3: Verify that the pod is created

While Kubernetes formally defines five core phases, the kubectl get pods command often displays granular status reasons, like ContainerCreating or CrashLoopBackOff, to provide immediate insight into the pod's current state. To list all Pods in the cluster:

kubectl get pods

You should see demo-pod with a status such as Pending, Running, Succeeded, Failed, or Unknown. Once the image is pulled and the container starts, the status should be Running.

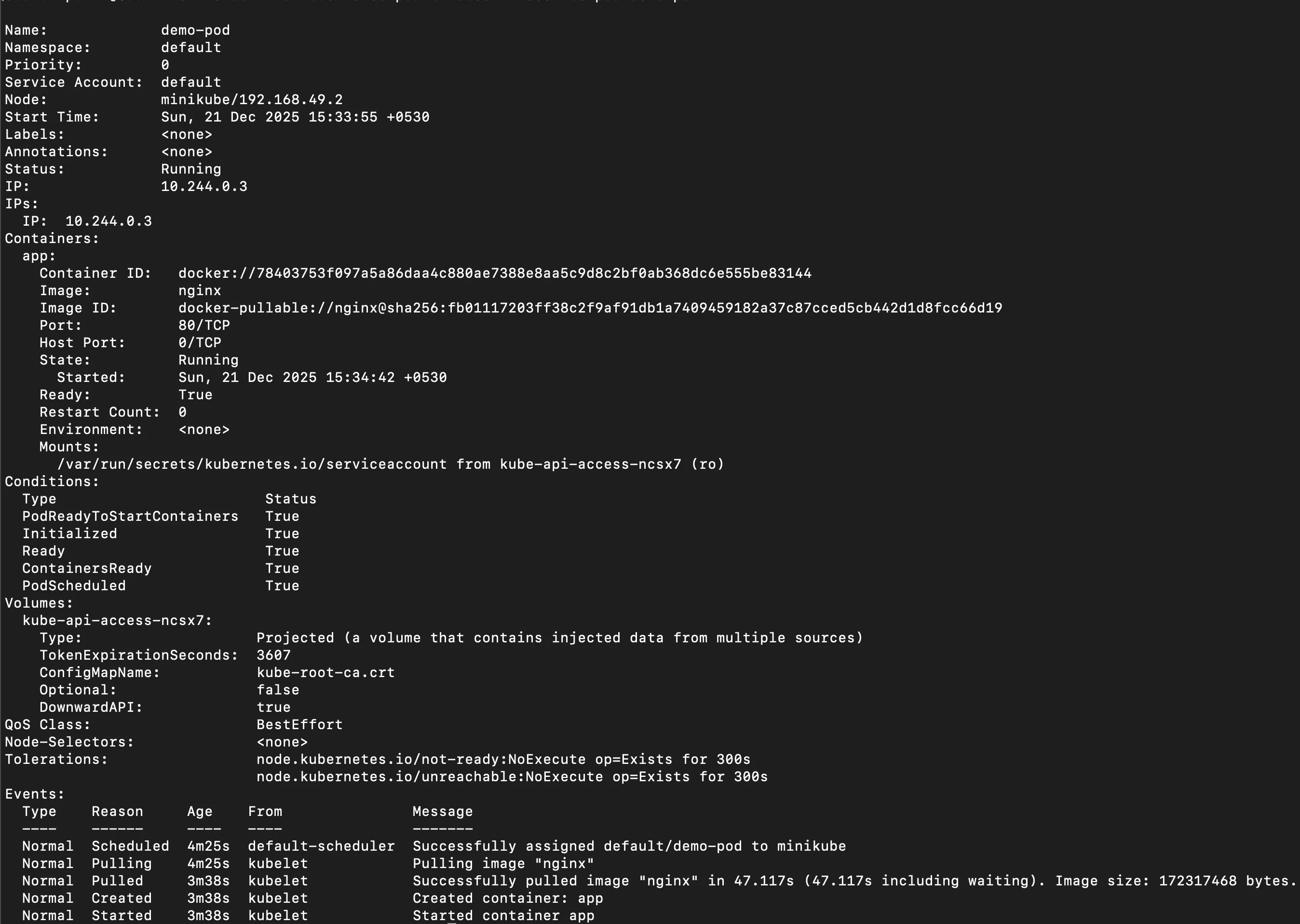

Step 4: Inspect Pod details

Get detailed information about the Pod:

kubectl describe pod demo-pod

This command helps you understand why a Pod is in its current state by showing scheduling details, container status, and events. It's most useful for quick Pod-level debugging before diving into logs or node issues.

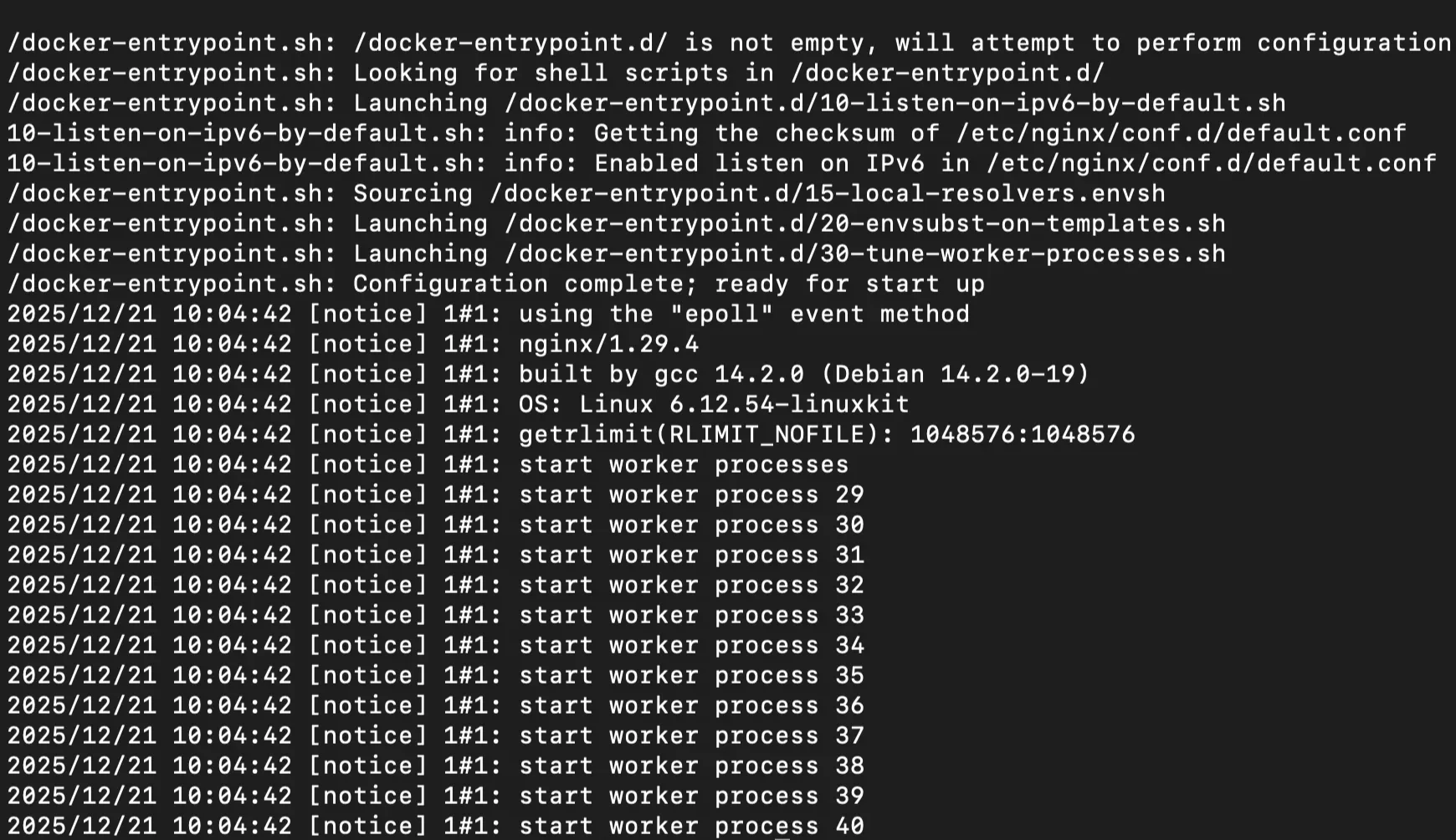

Step 5: View pod logs

Logs are typically the first place to look when troubleshooting application startup issues or runtime errors.

To inspect the container's stdout and stderr output, use:

kubectl logs demo-pod

For a deeper, step-by-step guide to viewing, filtering, and troubleshooting Kubernetes logs (including multi-container Pods and common pitfalls), see the SigNoz Guide to Kubectl Logs.

Step 6: Execute into the Pod

Open an interactive shell inside the running container to inspect processes, files, and network behaviour in real time.

kubectl exec -it demo-pod -- sh

Once inside the container shell, run simple commands to verify the app and environment. If everything is working correctly, you should see the default “Welcome to nginx!" HTML page.

curl localhost:80

# Output

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Welcome to nginx!</title>

<style>

html { color-scheme: light dark; }

body { width: 35em; margin: 0 auto;

font-family: Tahoma, Verdana, Arial, sans-serif; }

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Welcome to nginx!</h1>

<p>If you see this page, the nginx web server is successfully installed and

working. Further configuration is required.</p>

<p>For online documentation and support please refer to

<a href="http://nginx.org/">nginx.org</a>.<br/>

Commercial support is available at

<a href="http://nginx.com/">nginx.com</a>.</p>

<p><em>Thank you for using nginx.</em></p>

</body>

</html>

Step 7: Delete the pod

Clean up the resources by deleting the Pod:

kubectl delete -f demo-pod.yaml

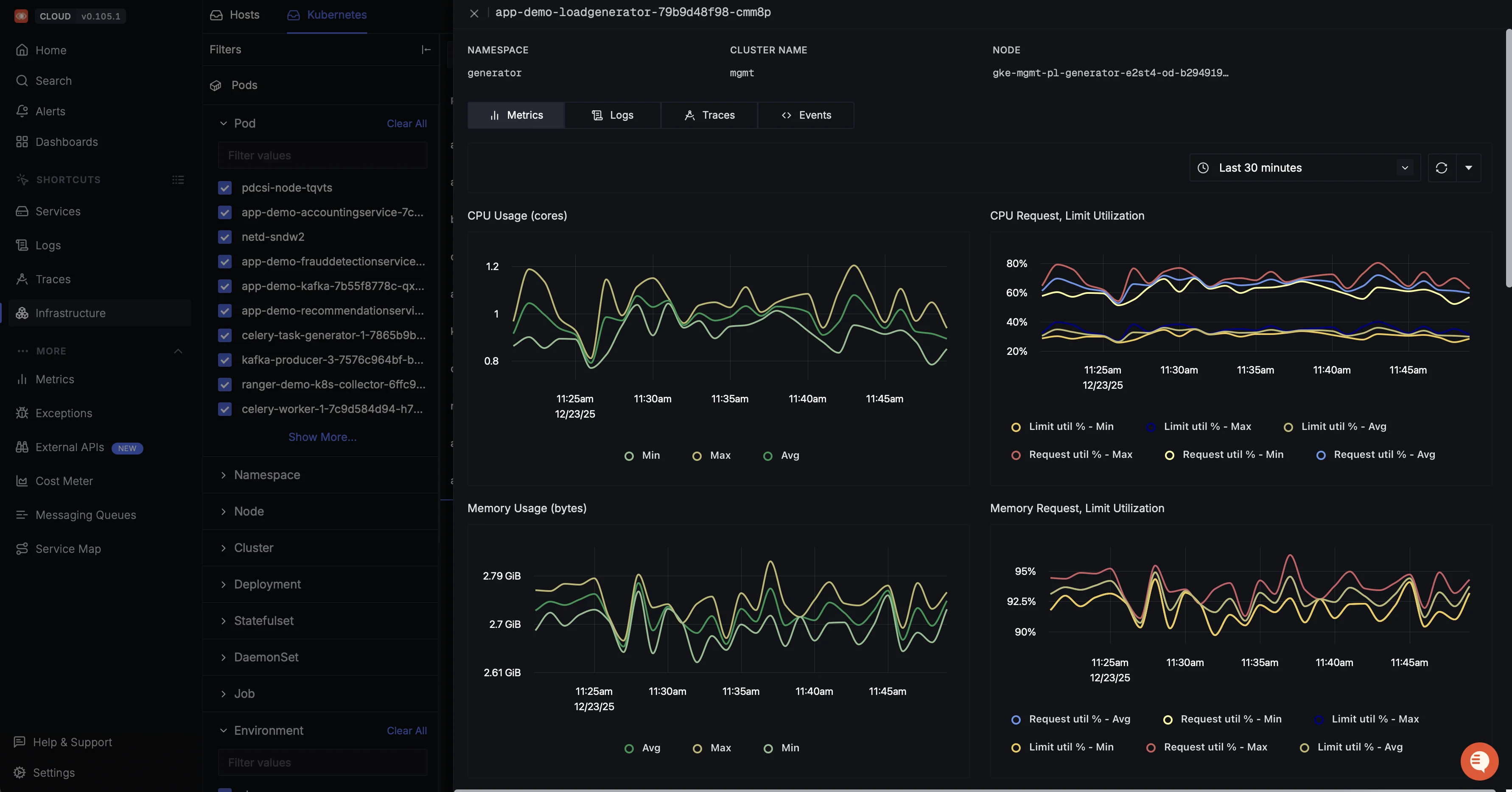

From kubectl to Observability: Monitoring Pod Health with OpenTelemetry and SigNoz

Monitoring Kubernetes Pods goes beyond checking their status with kubectl. You need continuous visibility into resource usage, restarts, failures, and performance trends across all running Pods.

OpenTelemetry (OTel) provides a foundation by standardizing how Kubernetes emits metrics and logs, from Pods, containers, and nodes. This ensures Pod health signals are collected consistently across clusters without vendor lock-in.

SigNoz builds on this foundation as an OpenTelemetry-native observability platform, turning raw OTel data into actionable insights through built-in Kubernetes dashboards.

SigNoz provides out-of-the-box visibility into the core signals that define Pod health:

- Infrastructure Metrics: Track CPU and memory usage at the Pod and container level and compare them against configured requests and limits. This helps identify noisy neighbours, understand Quality of Service (QoS) behaviour, and prevent resource contention. Learn more in the Kubernetes Metrics Documentation.

- Pod Logs: Automatically collect and analyze logs from every container in a Pod. This makes it easy to debug failures such as

CrashLoopBackOfforOOMKilledby inspecting the final logs emitted before a restart or termination. See the guide on Collecting Kubernetes Pod Logs.

With these signals correlated in a single view, SigNoz makes it easy to understand Pod behaviour and troubleshoot issues without stitching together multiple tools.

Best Practices for Managing Pods

Poorly configured Pods are a common source of outages and resource contention. These best practices address the most common operational pitfalls.

Set CPU & Memory Requests/Limits: Always define resource requests and limits to ensure predictable scheduling, prevent noisy neighbours, and avoid unexpected OOM kills.

Use Liveness & Readiness Probes: Readiness probes control traffic flow, while liveness probes enable self-healing by automatically restarting unhealthy containers.

Run Pods with Least Privilege: Avoid running containers as root, drop unnecessary capabilities, and restrict permissions using security contexts to reduce blast radius.

Use Controllers, Not Naked Pods: Deploy Pods via Deployments, StatefulSets, or DaemonSets to get automatic restarts, scaling, and safe rolling updates.

Externalize Config and Secrets: Store configuration in ConfigMaps and sensitive data in Secrets to keep images immutable and simplify updates without redeployments.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a Kubernetes Pod vs Cluster?

A Pod is the smallest building block of Kubernetes workloads. It is a lightweight wrapper around one or more containers that run together on the same node, sharing IP addresses, ports, and volumes for seamless communication. In contrast, a Cluster is the full Kubernetes environment: a group of interconnected nodes (physical or virtual machines) orchestrated by a control plane to manage Pods at scale, handle scheduling, scaling, and high availability across the entire system.

Can we create a Pod without a container?

No, you cannot create a Kubernetes Pod without at least one container. A Pod is the smallest deployable unit in Kubernetes and is fundamentally designed to encapsulate one or more tightly coupled containers that share resources like storage and networking. Attempting to define an empty Pod will result in validation errors during creation.

What are the lifecycle stages of a Pod?

Pods progress through phases: Pending (resources allocated, but not yet running), Running (at least one container active), Succeeded (all containers terminated successfully), Failed (a container crashed irreparably), or Unknown (status unreadable). Use kubectl describe pod <name> to track and debug transitions.

How many Pods are in a Kubernetes Node?

The number of Pods per Node isn't fixed but is limited by configuration and resources. By default, Kubernetes allows up to 110 Pods per Node. This can be adjusted via the Kubelet flag --max-pods or cluster settings, often up to 250 in optimized setups. Always monitor Node CPU, memory, and network capacity to avoid overload.

Hope we answered all your questions regarding what is a Kubernetes Pod.

You can also subscribe to our newsletter for insights from observability nerds at SigNoz, get open source, OpenTelemetry, and devtool building stories straight to your inbox.